The Fabaceae Family, also widely known as the legume or pea family, stands as a botanical giant, holding the prestigious title of the third-largest plant family globally. Often referred to by its former name, Leguminosae, this family is instantly recognizable thanks to its unique flowers and, most notably, its signature fruit: the legume. Across diverse landscapes, from cultivated gardens to wild trails, members of the Fabaceae family are ubiquitous, showcasing their remarkable adaptability and diversity. At the Hoyt Arboretum, our living collection proudly features several noteworthy species from the Fabaceae family, while in our broader region, legumes frequently appear as common weeds along trails, lawns, and roadsides.

Let’s delve into some captivating facts that highlight the significance of the legume family:

- Globally, the Fabaceae family boasts an impressive count of approximately 750 genera and 19,000 species. This vast number positions it as the third largest plant family worldwide, surpassed only by the Orchidaceae (orchid family) and Asteraceae (daisy or sunflower family). Within the 2018 Pacific Northwest Flora, the Fabaceae family is represented by 28 genera and 352 taxa, demonstrating a significant presence in this region alone. The Hoyt Arboretum’s collection includes 16 genera and 21 species, offering a glimpse into the family’s local diversity.

- The historical name, Leguminosae, directly alludes to the family’s characteristic legume fruits. Conversely, the modern name, Fabaceae, originates from the genus Faba, now considered obsolete and integrated into the genus Vicia. In Latin, “faba” translates to “bean,” underscoring the family’s connection to edible beans, exemplified by Vicia faba, the scientific name for fava or broad beans.

- A defining feature of the Fabaceae family is that all its members produce legume fruits. Botanically, a legume is a dry fruit, derived from a single carpel, that at maturity opens along two lines of dehiscence to release its seeds. While some legumes are consumed in their immature, green forms (like green beans, sweet peas, and sugar snap peas), others develop into a specialized legume type called a loment. A loment is simply a legume that is constricted between the seeds, segmenting it into pod-like sections.

- The culinary world owes much to the Fabaceae family, as many legumes are edible when cooked. Beyond those already mentioned, staples like black beans, pinto beans, lima beans, and soybeans are all legumes. Furthermore, chickpeas (or garbanzo beans), split peas, and lentils, collectively known as pulses, also belong to this family. However, it’s crucial to note that not all Fabaceae family members are safe for consumption. Lupines (Lupinus genus) can be toxic if ingested, and plants in the Astragalus genus, commonly called locoweed, are highly poisonous to livestock and potentially humans.

- Legumes are renowned for their ability to form symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria. This partnership is ecologically significant as these bacteria convert atmospheric nitrogen into forms plants can use, enriching the soil. Consequently, cover crops like alfalfa, crimson clover, and red clover, all from the Fabaceae family, are frequently employed as “green fertilizers” to naturally boost soil nitrogen levels.

- Certain members of the Fabaceae family possess a unique structure called a pulvinus, located at the base of their leaves, at each petiole and petiolule. This pulvinus, resembling a joint-like thickening, facilitates the fascinating movement of leaflets, allowing them to open during the day and close at night, a phenomenon observable in the silk tree (Albizia julibrissin) at the Arboretum. In some species, the pulvinus also triggers leaflet closure in response to touch. The sensitive plant (Mimosa pudica) exemplifies this touch-sensitive response, speculated to be a mechanism to reduce water loss during windy conditions or deter herbivores by making the plant appear less appealing.

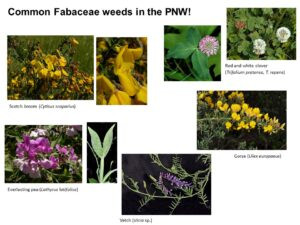

- Paradoxically, the Fabaceae family includes some of the most pervasive weeds in the Pacific Northwest. Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius) is widespread in prairies, forest edges, and disturbed areas, including along transportation corridors. Gorse (Ulex europaeus) aggressively invades coastal regions of Oregon, while black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) can spread in riparian zones. Vetch (Vicia spp.), peavines (Lathyrus spp.), and red and white clover (Trifolium pratense and T. repens) are common weedy species found along trails and in grassy areas.

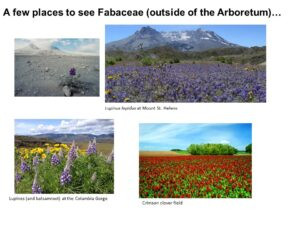

- In a remarkable display of resilience, the dwarf prairie lupine (Lupinus lepidus), a member of the Fabaceae family, was among the first seed plants to re-establish in the Mount St. Helens blast zone after the 1980 eruption. Its relatively large seeds, which survived buried in the soil, were not dispersed by wind. Instead, pocket gophers churning the soil unearthed these seeds, facilitating their germination and rapid colonization of the devastated landscape. The growth of Lupinus lepidus, coupled with its nitrogen-fixing bacteria, played a crucial role in replenishing essential nutrients in the nutrient-depleted blast zone.

- Perhaps surprisingly to some, peanuts (Arachis hypogaea) are also members of the Fabaceae family. Peanut plants exhibit an unusual reproductive strategy: their flowers develop near the ground and, after self-pollination, the developing fruits are uniquely geocarpic, meaning they push themselves into the ground – first vertically, then horizontally. The legume fruits then mature underground until harvest.

Key Characteristics of the Fabaceae Family:

The Fabaceae family exhibits a range of growth forms, encompassing trees, shrubs, and herbs, united by a set of shared botanical characteristics:

- Nitrogen Fixation: A significant ecological trait is their frequent symbiotic association with nitrogen-fixing bacteria, leading to the formation of visible nodules on their roots. This relationship enhances soil fertility and reduces the need for synthetic fertilizers.

- Leaves: Leaves are typically arranged alternately on the stem and are often compound, taking forms such as pinnately compound, palmately compound, or trifoliate. A notable exception is the genus Cercis, which displays simple leaves. Leaflet margins are typically smooth.

- Flowers: Fabaceae flowers are bisexual, containing both stamens and a pistil, and exhibit either radial or bilateral symmetry. They possess 5 fused sepals and 5 petals, which may be similar or differentiated in shape and size.

- Stamens and Pistil: The number of stamens can vary from many to a reduced count of 10. When 10 stamens are present, they may be diadelphous, meaning 9 are fused together, with 1 remaining free. The pistil is composed of a single carpel, and the ovary is superior.

- Fruit: The defining fruit type is a legume or loment, encapsulating the seeds within a dry pod that typically splits open upon maturity.

Subfamilies within Fabaceae:

Botanists often categorize the Fabaceae family into three subfamilies, each displaying distinct floral characteristics:

- Subfamily Mimosoideae: Members of this subfamily are characterized by flowers that resemble “poofs.” This appearance is due to their radial symmetry and numerous, prominent stamens, while the petals are small, often inconspicuous, and unfused. The showy “poof” effect is created by the many exserted stamens.

- Subfamily Caesalpinoideae: This group features flowers with bilateral symmetry and unfused petals. Close observation reveals that the uppermost petal, known as the standard or banner petal, is positioned in front of the lateral wing petals and is often smaller than them. The two lower petals may project forward but remain unfused. Typically, this subfamily has 10 unfused stamens.

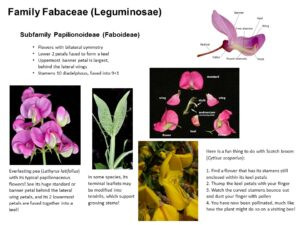

- Subfamily Papilionoideae (Faboideae): Representing the largest subfamily within Fabaceae, Papilionoideae flowers often evoke the shape of butterflies, hence the term “papilionaceous flowers.” These flowers are bilaterally symmetrical, with the uppermost petal usually being the largest and positioned behind the lateral wing petals. The two lowermost petals are fused together, forming a keel, reminiscent of a boat’s keel. They also possess 10 stamens, frequently diadelphous, arranged in two groups – typically nine fused stamens and one free stamen.

Discover Fabaceae at Hoyt Arboretum:

For those visiting the Hoyt Arboretum, a significant collection of pea or legume family trees is located at the intersection of the Overlook, Wildwood, and Hawthorn Trails, near the hilltop water tank. Throughout much of the year, these trees display intriguing and showy flowers and/or dangling legume fruits, providing an excellent opportunity for observation and study. Visitors are encouraged to examine these specimens and try to identify which subfamily each tree belongs to, applying the characteristics described.

About the Author:

Dr. Mandy Tu is the Plant Taxonomist and Herbarium Curator at Portland Parks & Recreation’s Hoyt Arboretum. Her role involves collecting plant specimens, verifying tree identification within the Arboretum, and assisting natural area managers in the Portland region with plant identification. Dr. Tu holds a B.S. in Botany from the University of Washington and a Ph.D. in Plant Biology from the University of California at Davis. She is an experienced educator, having led numerous plant identification courses and workshops for both botanical professionals and plant enthusiasts.

References:

- Baldwin, B. et al. (eds.). 2012. The Jepson Manual, Vascular Plants of California, 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Hitchcock, C.L. and A. Cronquist. 2018. Flora of the Pacific Northwest: An Illustrated Manual, 2nd Edition. Edited by D.E. Giblin, B.S. Legler, P.F. Zika, and R.G. Olmstead. University of Washington Press, Seattle, WA.

- Zomlefer, W.B. 1994. Guide to Flowering Plant Families. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC.

Image Credits: