The Solanaceae family, commonly known as the nightshade family, is a fascinating and diverse group of plants encompassing around 2,600 species across the globe. This family showcases an incredible range of forms, from humble herbs and sprawling shrubs to towering trees and climbing vines. What truly sets the nightshade family apart is its dual nature: it includes both incredibly toxic plants and some of the most vital food crops in human diets.

While the name “nightshade” often evokes images of dangerous poisons – and indeed, plants like deadly nightshade and Jimson weed live up to this reputation – Solanaceae also gifts us with staples like potatoes, tomatoes, and chili peppers. Even tobacco, a plant renowned for its potent toxins and addictive properties, belongs to this family and is cultivated on a massive scale for both recreational drug use and as an agricultural insecticide, leveraging its nicotine content. Beyond these well-known examples, the nightshade family serves as a source for several pharmaceuticals, highlighting its complex relationship with human health and industry.

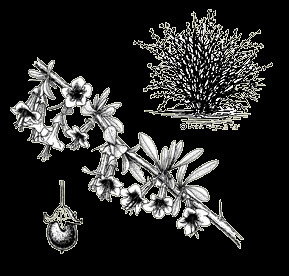

Sacred Datura: A Closer Look at Datura wrightii

Sacred Datura flower, white funnel shape, with spiky seed pod, illustrating Datura wrightii, also known as Jimson weed or Angel's Trumpet, a toxic plant from the nightshade family. Sacred Datura flower, white funnel shape, with spiky seed pod, illustrating Datura wrightii, also known as Jimson weed or Angel's Trumpet, a toxic plant from the nightshade family. |

|---|

Datura wrightii (synonym D. meteloides), known by common names such as sacred datura, Jimson weed, angel’s trumpet, and devil’s weed in English, and toloache grande, tecuyaui, belladona in Spanish, exemplifies the intriguing characteristics of the Nightshade Family Solanaceae.

Description

Jimson weed, a prevalent English name for Datura wrightii, is a perennial herb that can reach heights of 2 to 5 feet (0.60-1.5 m) and spread to several feet in width, thanks to its substantial tuberous root. Its foliage is characterized by a dark green hue and a sticky texture, emitting a pungent, unpleasant odor when crushed. The plant produces striking, funnel-shaped white flowers, measuring approximately 6 inches in length and 3 inches in width (15 x 8 cm). These blossoms unfurl at dusk, releasing a potent, sweet fragrance into the night air. Flowering occurs sporadically throughout the warm seasons if sufficient soil moisture is available, peaking in late summer with a profusion of blooms. The fruit is a spiny, golf-ball-sized capsule containing numerous disk-shaped seeds, each carrying the potential for new growth – and potential danger.

Range

Datura wrightii has a distribution range spanning from central California to Texas and Mexico, extending into the northern regions of South America, demonstrating its adaptability to varied warm climates.

Notes

All parts of Datura wrightii harbor a cocktail of toxic alkaloids, including scopolamine, which, ironically, is found in some medications for colds and nausea. Historically, shamans across diverse cultures have utilized datura in ritualistic practices to induce visions. However, this use carries extreme risks. The potency of individual plants can vary significantly, and human tolerance to these toxins also differs widely. Despite widespread warnings, accidental poisonings from ingesting Datura wrightii continue to occur annually, some with fatal consequences.

Beyond its toxicity, sacred datura possesses ornamental appeal, provided ample space is available to accommodate its size and its seasonal dormancy is acceptable. Hawkmoths play a crucial role in pollinating its flowers and also deposit their eggs on the foliage. The resulting caterpillars, known as “hornworms” within the nightshade family solanaceae, sequester the plant’s toxins, rendering themselves toxic to potential predators – a remarkable example of ecological adaptation.

The large leaves of Datura wrightii may seem counterintuitive for a desert-adapted plant, yet it flourishes during the hottest periods, even when soil moisture appears scarce. This adaptation is discussed further in the Plant Ecology chapter of “The Sonoran Desert: A Natural History,” highlighting the plant’s sophisticated survival strategies.

Datura wrightii distinguishes itself as the only perennial datura in its region. Its annual counterparts, Datura discolor (desert thorn apple, toloache) and Datura stramonium (jimson weed, hierba del diablo), are smaller in stature, yet share the characteristic toxicity of the nightshade family.

Wolfberries: Exploring the Lycium Genus

Lycium species, commonly known as wolfberries or boxthorns, present another facet of the nightshade family solanaceae. Spanish common names include frutilla (generic) and, for Lycium berlandieri, barchata, josó, hosó cilindrillo, tomatillo.

Description

The Lycium genus in the Sonoran Desert region comprises several species of densely branched, often spiny shrubs. These shrubs typically shed their leaves during dry seasons, an adaptation to conserve water. They vary in size from approximately 2 feet (60 cm) to over 8 feet (2.4 m) in height and can spread considerably, influenced by species and water availability. Leaves are most prominent during the cooler months. They produce abundant small flowers, ranging in color from greenish to purplish, which give way to pea-sized red berries resembling miniature tomatoes – an enticing, albeit sometimes deceptive, fruit.

Wolfberry shrub, dense and spiny, with small red berries, illustrating Lycium pallidum, a drought-tolerant plant from the nightshade family. Wolfberry shrub, dense and spiny, with small red berries, illustrating Lycium pallidum, a drought-tolerant plant from the nightshade family. |

|---|

Range

The Lycium genus is cosmopolitan, encompassing around 100 species distributed across warm-temperate and subtropical habitats globally. Approximately 15 species are found within the Sonoran Desert, underscoring their ecological significance in arid environments.

Notes

Almost every corner of the Sonoran Desert is home to at least one Lycium species. The floral structure suggests bee pollination, and bees are indeed frequent visitors. However, butterflies and hummingbirds also contribute to pollination, attracted by nectar and pollen. Birds are particularly fond of the berries, and humans also value these small, flavorful fruits as a snack. However, a word of caution for the squeamish: Lycium berries often harbor insect larvae. This fact does not deter the Seri people, for whom these larvae are simply considered “live things,” a testament to cultural perspectives on food and nature.

Interestingly, lac insects (Tachardiella spp.) can be found on wolfberries, as well as on creosote bushes, indicating a broader ecological role within the desert ecosystem. A related species, the Indian lac insect, is commercially harvested on a large scale for the production of shellac and varnish, demonstrating the diverse economic and ecological connections within the nightshade family solanaceae and its related species.