As a new animated rendition of The Addams Family prepares to charm audiences, it’s the perfect moment to delve into the captivating history of this iconic franchise and, more specifically, the enduring appeal of one of its most peculiar members: Thing. Long before CGI wizardry became commonplace, bringing Thing, the disembodied hand, to life in the early 1990s Addams Family films presented a unique and delightful challenge for filmmakers.

In 1991, director Barry Sonnenfeld took the helm for The Addams Family, marking the beginning of a beloved cinematic journey. Visual effects supervisor Alan Munro was tasked with the crucial role of making Thing a believable and engaging character. In a fascinating account, Munro details the ingenious blend of practical effects, puppetry, and optical techniques that resulted in Thing’s memorable on-screen presence.

Let’s journey back to Scott Rudin’s office in 1990, as Munro humorously recounts his initial meeting and the seemingly daunting question posed to him: How would he create Thing?

Alan Munro: My foray into the world of The Addams Family commenced in the summer of 1990. There I was, in Scott Rudin’s office, basking in the sunshine, alongside Scott and director Barry Sonnenfeld. The mission? To audition for the esteemed position of visual effects supervisor. Naturally, the burning question on Scott and Barry’s minds was, “How will you bring Thing to life?”

“Truthfully,” I responded, “I haven’t the foggiest idea. And at this juncture, I’m not overly concerned. Our first order of business is to define Thing’s essence, his purpose within the narrative. Once we grasp that, the mechanics of his animation will fall into place.”

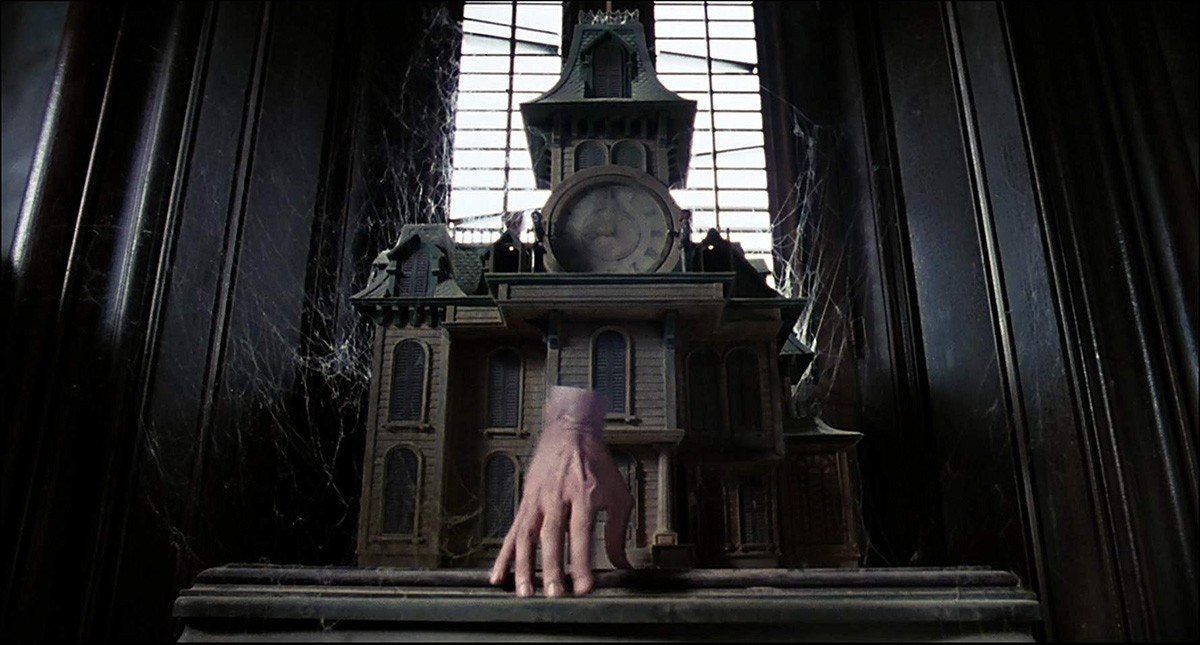

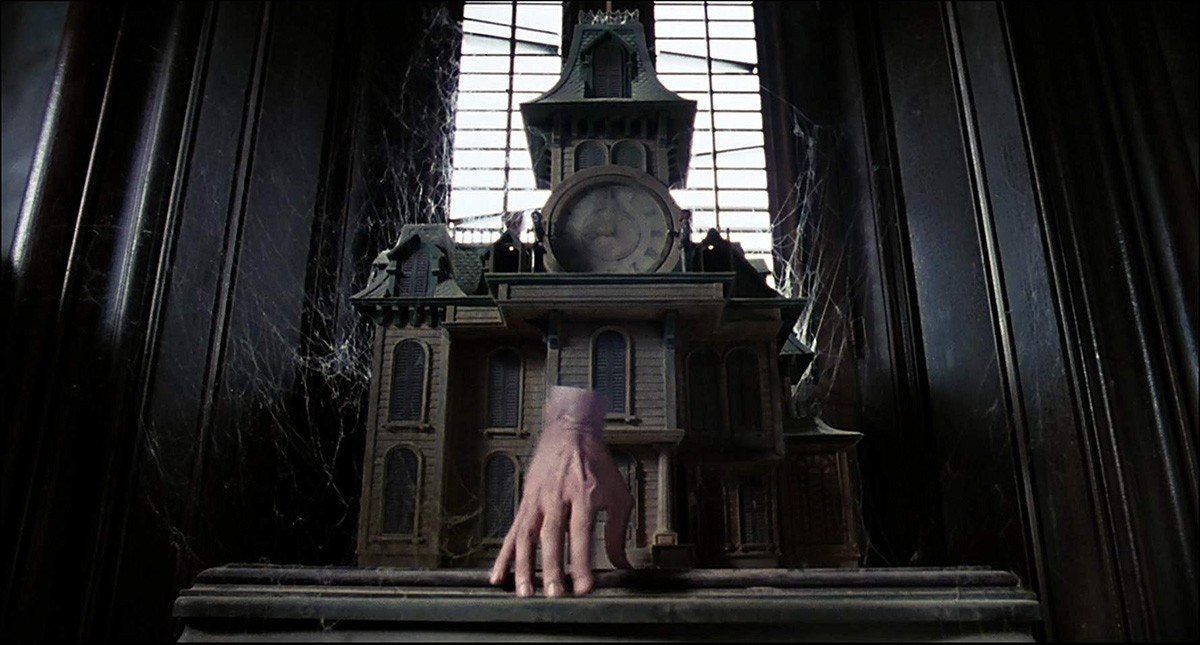

Image: Thing, the iconic disembodied hand character, scurrying playfully in The Addams Family film from 1991, showcasing the practical visual effects.

Image: Thing, the iconic disembodied hand character, scurrying playfully in The Addams Family film from 1991, showcasing the practical visual effects.

Intrigued by my approach, they probed further, “Okay, then enlighten us – who is Thing?”

“Within the script,” I elaborated, “Thing is perceived as a family pet, akin to a hamster, darting around the house. However, I envision Thing as something far grander, something magical. He should embody the spirit of Fred Astaire.”

“Fred Astaire?” they echoed, perhaps slightly bewildered.

I continued, “Consider Astaire’s characters. They exist within the natural world, yet seem unbound by its constraints. His grace, his elegance, his effortless movements, defy gravity. When Fred dances up walls and across ceilings, it appears utterly natural. That’s the essence Thing must capture – natural yet unnatural, bound yet unbound.”

Evidently, my vision resonated, and I secured the role.

While I may have contributed to shaping Thing’s character, the visual conception of Thing belongs to production designer Richard MacDonald, with a nod to an unexpected source – a children’s birthday party puppeteer.

To me, the sophisticated charm of Fred Astaire suggested a starched white French cuff, fastened with an Addams family crest cufflink. The interior of the cuff, I imagined, would be shrouded in shadow, concealing the unseen. Simple, elegant, and subtly magical.

“Thing in a cuff? Preposterous!” designer MacD (Barry’s moniker for MacDonald) retorted. “It’s like adorning a hat with another hat.”

“No,” I corrected, “It’s akin to placing a cuff on a wrist. But let’s set that aside. What’s your vision for Thing’s appearance?”

“The wrist’s interior should resemble a teacup,” MacD declared.

“A teacup?” I responded, genuinely puzzled.

“When gazing into an empty teacup,” MacD elaborated, “the bottom remains elusive, hidden from view.”

Image: A closer look at Thing’s design in The Addams Family movie, highlighting the “teacup wrist” concept and starched white cuff, blending elegance with the bizarre.

Image: A closer look at Thing’s design in The Addams Family movie, highlighting the “teacup wrist” concept and starched white cuff, blending elegance with the bizarre.

MacD’s teacup analogy alluded to the illusion of infinite depth created by the smooth, porcelain slope – perhaps more apparent after a drink or two. He believed this visual metaphor would translate effectively to Thing, especially if constructed as a puppet.

“Whether ‘correct’ or not, Thing will not be a puppet,” I interjected. “Thing will be portrayed by a real human hand, with the body optically removed.”

“Absolutely not,” MacD insisted. “He will be a puppet. I’ve already engaged a puppeteer.”

“This,” I admitted, “I have to witness.”

Image: Thing gracefully moving across a surface in The Addams Family (1991), demonstrating the puppeteer’s initial concept for bringing the character to life.

Image: Thing gracefully moving across a surface in The Addams Family (1991), demonstrating the puppeteer’s initial concept for bringing the character to life.

The following day, a gentleman of amiable disposition, clad in green-checkered trousers and carrying an orange checkered carpet bag, arrived at my office. From this bag, he produced a cassette player and placed it on my desk. Next, he unveiled two marionette control bars, each connected to an articulated wooden hand by a dozen strings. For the ensuing three minutes, the wooden hand gracefully waltzed across my office carpet to the strains of The Blue Danube. True to MacD’s vision, the hand featured a hollowed-out teacup wrist, cleverly concealing the string attachments. As the waltz concluded, the puppeteer, with a pronounced Czech accent, inquired if I wished to see a goat dance the polka. I politely declined. Before departing, he crafted a charming balloon dachshund for me.

Fortunately, I had invited Barry, Scott, and others to witness this demonstration.

The verdict? Thing would indeed sport a teacup wrist, but MacD’s influence on effect execution had reached its limit.

Sometimes, strategic retreats pave the way for ultimate victories.

Image: A puppet hand demonstration for Thing in The Addams Family, showcasing an early approach that was eventually replaced by live-action performance for greater realism.

Next came the crucial task of casting. My initial choice for Thing was my friend, Don McLeod, a brilliant mime and protégé of Marcel Marceau. Don was perhaps best known as the “American Tourister Gorilla” from those commercials where he attempted to breach suitcases. Early camera tests featuring Don were impressive in terms of performance, but his hand, unfortunately, lacked the desired aesthetic. Fred Astaire’s movements require Fred Astaire’s elegant form. Don, regrettably, didn’t quite fit the visual bill. Exit Don.

I compiled a list of alternatives. Beyond mimes, magicians seemed the most logical choice – individuals trained in intricate hand movements. A casting call went out to two dozen sleight-of-hand artists. The day they all responded remains vividly in my memory. Never before had I been asked for so many quarters, divined so many playing cards, or had so many eggs extracted from my ear. Ultimately, one candidate stood out: Christopher Hart.

Christopher Hart had served as an assistant to David Copperfield and bore a striking resemblance to the famed magician, even standing in for Copperfield in some illusions. Beyond his magic skills, Chris was tall, intelligent, athletic, and possessed remarkably expressive hands. Moreover, in a room full of magicians, Chris seemed refreshingly… normal.

Image: Actor Christopher Hart portraying Thing in The Addams Family films, chosen for his expressive hands and magician’s dexterity, bringing a unique physicality to the character.

Image: Actor Christopher Hart portraying Thing in The Addams Family films, chosen for his expressive hands and magician’s dexterity, bringing a unique physicality to the character.

With our Thing cast, the next hurdle was achieving the effect. In a pre-computer graphics era, techniques relied on practical methods and optical printers.

I turned to Pete Kuran, a long-time collaborator and visual effects innovator. We devised a two-pass shooting technique: once with Chris and once without. For front, top, and profile shots, Chris would lie prone on a mechanic’s dolly, arm extended, clad in a black sleeve. A prosthetic wrist extension, angled upwards, created the illusion of a body positioned above. For shots from behind, or when Thing turned, Chris would be positioned above the camera with a prosthetic around his actual wrist, defining the edge of the effect.

In post-production, Chris’s body would be meticulously removed frame-by-frame using rotoscoping, a painstaking animation process. Pete Kuran, having pioneered the Star Wars lightsaber effect, was a recognized master of rotoscoping. The background plate, shot without Chris, would then seamlessly replace the areas where Chris had been removed, composited together using an optical printer. A simple concept, yet deceptively complex in execution.

These optical shots featuring a real hand were interspersed with shots of hand puppets – not marionettes, but mechanical hands crafted from lifelike latex, designed for specific actions (Thing as a golf tee, for instance). For this specialized work, I enlisted Dave Miller, a collaborator from my Nightmare on Elm Street days.

This approach allowed us to maintain an element of mystery, leaving the audience to wonder, shot by shot, about the techniques employed.

Image: David B. Miller meticulously crafting mechanical hand puppets for The Addams Family, showcasing the blend of practical and performance-based techniques used in the film.

Image: David B. Miller meticulously crafting mechanical hand puppets for The Addams Family, showcasing the blend of practical and performance-based techniques used in the film.

On the first day of production, we positioned Chris beneath a table for the chess scene with Gomez. Camera stability was paramount for our two-pass technique. Unfortunately, the chess table wobbled. Extensively. Stabilizing it proved to be an ordeal, transforming the set into a web of guy-wires. Barry nearly succumbed to a nervous breakdown. Following this initial chaos, I established my own camera unit, effectively directing every shot featuring Thing in the film. This isn’t to claim sole authorship of Thing’s portrayal, as it was a collaborative effort with Barry Sonnenfeld, Chris Hart, Chuck Comisky, and numerous other talented crew members. It simply reflects the logistical organization of the production.

Explore Alan Munro’s extensive VFX credits on IMDB.