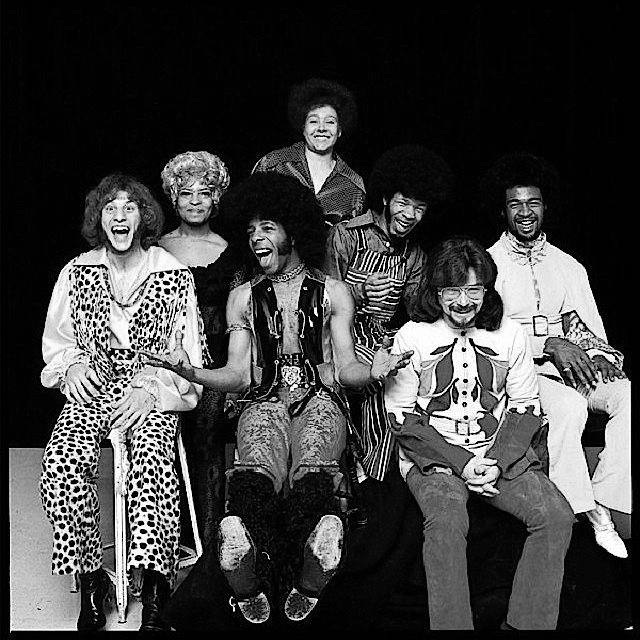

Sly and the Family Stone stand as titans of American music, their innovative fusion of funk, soul, and rock reshaping the sonic landscape of the late 1960s and early 1970s. While their discography boasts numerous hits, “Everyday People” remains an enduring anthem, a testament to their inclusive ethos and a reflection of a pivotal moment in American social history. This exploration delves into the history of Sly and the Family Stone, charting their rise, the context surrounding “Everyday People,” and the song’s lasting impact, offering a comprehensive look beyond the surface of this iconic track.

Sly and the Family Stone performing live

Sly and the Family Stone performing live

From Diverse Roots to a Revolutionary Sound

The story of Sly and the Family Stone is rooted in the diverse backgrounds of its members, a microcosm of the very unity they would champion in their music. The Stone family, at the heart of the group, had musical talent running deep. Sylvester Stewart, later known as Sly Stone, and his siblings Freddie and Rose, were all steeped in gospel music from a young age. Their upbringing provided a foundation in musicality, but Sly’s ambitions stretched beyond genre limitations.

Before forming the Family Stone, Sly Stone honed his skills in the music industry, working as a record producer and radio DJ in the San Francisco Bay Area. This experience exposed him to a wide spectrum of musical styles, from R&B to the burgeoning rock scene. He recognized a growing divide in music, categorized along racial lines, and envisioned a sound that would transcend these boundaries. As Sly himself proclaimed, “I explained to ’em that there ain’t no Black and there ain’t no white and if it comes down to that there ain’t nobody Blacker than me. There ain’t nobody Blacker than Syl!”

He sought to create music that resonated with the burgeoning counterculture in San Francisco, blending the melodic innovation of The Beatles, the lyrical depth of Bob Dylan, and the raw funk of James Brown and Otis Redding. This ambition led him to assemble a band as diverse as his musical vision.

Jerry Martini, a white saxophone player, brought a background in R&B from his time with George and Teddy and the Condors. Greg Errico, also white, had experience in soul and rock drumming with Freddie Stone’s earlier band, Freddie and the Stone Souls. Cynthia Robinson, a Black trumpet player, had a history in the blues and R&B circuit. Larry Graham, a Black bassist, contributed a unique, percussive slap bass style that would become a signature element of the Family Stone sound. Rose Stone, Sly’s sister, added keyboards and vocals, further enriching the band’s dynamic.

This interracial and gender-integrated lineup was revolutionary for the time. In an era of stark racial segregation and limited opportunities for women in instrumental roles in rock music, Sly and the Family Stone presented a powerful image of unity and equality, mirroring the message they would soon convey in their music.

Early performances at venues like the Winchester Cathedral showcased their versatility. They initially played covers, blending soul and R&B hits with their own burgeoning original material. Their shows were designed to highlight each member’s individual talents, creating a dynamic and engaging live experience. Instrumental jams like “The Riffs” demonstrated their musical prowess, and the seamless transitions between songs kept audiences captivated.

The First Steps Towards Stardom: “Dance to the Music”

Despite their captivating live performances, early recordings didn’t translate into immediate commercial success. Their debut album, A Whole New Thing, while lauded by fellow musicians and critics for its innovation, failed to chart. Record executives at CBS, however, remained convinced of their potential. Clive Davis and David Kapralik urged Sly to create something more accessible, a danceable pop song that could break through to a wider audience.

Initially resistant, Jerry Martini and others in the band viewed commercial compromise with suspicion. However, Sly delivered “Dance to the Music” in 1968, a track that would become their breakthrough hit. While Martini felt it was formulaic, rooted in “glorified Motown beats,” the song undeniably captured the zeitgeist.

“Dance to the Music” was a masterclass in hooks and arrangement. The song builds instrument by instrument, showcasing each member’s contribution. The “Ride, Sally, Ride” line echoed “Mustang Sally,” while the structure borrowed from King Curtis’ “Memphis Soul Stew.” A studio accident where Sly filled in forgotten lyrics with “boom boom boom” became an iconic vocal element, showcasing the band’s spontaneous creativity. Martini’s unexpected clarinet solo, born from a practical decision to bring a lighter instrument to a session, added a unique sonic signature to the track.

Sly Stone performing on stage

Sly Stone performing on stage

“Dance to the Music” became a Top 10 hit in the spring of 1968, propelling Sly and the Family Stone into the national spotlight. It influenced other artists, including The Temptations, who adopted elements of the Family Stone’s sound into their psychedelic soul hits like “Cloud Nine.” Psychedelic soul, pioneered by Sly and the Family Stone, became a dominant force in Black music, blending social commentary with funk rhythms and rock instrumentation.

The album Dance to the Music, while named after the hit single, mirrored the fate of their debut, achieving moderate success on the R&B charts but failing to break into the Top 100 pop albums. Nevertheless, “Dance to the Music” established Sly and the Family Stone as a force to be reckoned with, paving the way for greater recognition.

The Rise to Fame and the Genesis of “Everyday People”

The success of “Dance to the Music” led to significant opportunities, including a performance at the Fillmore East as the opening act for the Jimi Hendrix Experience in May 1968. However, this period also marked a shift within the band’s dynamic. According to Kapralik, Sly began to take center stage, diminishing the individual spotlights previously shared by band members. While not a complete shift initially, it foreshadowed Sly’s increasing dominance.

New York City became a crucial location for the band. Their residency at the Electric Circus exposed them to a different audience and further solidified their reputation as a dynamic live act. It was also during this period that Rose Stone officially joined the band, completing their classic lineup.

The relentless touring and pressures of fame, however, began to take a toll. Cocaine entered the band’s world, becoming a significant factor in their personal lives and creative trajectory. While initially perhaps seen as a stimulant and a tool for creativity, cocaine’s addictive nature and psychological effects would soon cast a shadow over the band’s trajectory.

Despite these growing challenges, Sly Stone’s songwriting remained incredibly potent. Following the less commercially successful Life album, which leaned more towards rock experimentation, Sly crafted “Everyday People.” This song emerged from a desire to create a standard, something universally relatable, like “Jingle Bells” or “Moon River.” He aimed for simplicity in melody and arrangement, with a message of unity that resonated deeply with the social climate of the late 1960s.

“Everyday People” is built upon Larry Graham’s iconic single-note bassline, a rhythmic foundation over which the song’s message unfolds. The song’s harmonic simplicity, utilizing only two chords, belies its intricate construction of hooks. The “na-na-na-na-na” chant, the horn lines, the “I am everyday people” chorus, and the “We got to live together” counter-vocal all contribute to its infectious and memorable quality.

“Everyday People”: An Anthem of Unity in a Divided Time

The lyrics of “Everyday People” directly address racial and social divisions. Released in November 1968, the month Nixon won the presidency on a platform that exploited racial anxieties, the song offered a contrasting vision of hope and reconciliation.

The verse addressing racial intolerance is particularly poignant:

“Sometimes I’m right and I can be wrong

My own beliefs are in my song

A rabbit’s got to run

A baby’s got to be born

Que sera, sera

Whatever will be, will be

The future’s not ours to see

Que sera, sera

What will be, will be”

This verse advocates for acceptance and understanding, acknowledging differences while emphasizing shared humanity. Sly’s philosophy at the time, as he articulated, was: “Either everything’s fair or nothing’s fair. Either everybody gets a chance to do what he wants or… you know what I mean?”

The song extends its message of inclusivity beyond race, addressing the hippie counterculture and societal judgments based on appearance:

“There is a yellow one that taught me so much in his colorful clothes

There’s a red one that can really make you stop and stare

There’s a black one that can hypnotize you with her big brown eyes

There’s a white one, he’s always tryin’ to keep you down”

While the optimism of “Everyday People” might seem somewhat naive in retrospect, particularly considering the social and political complexities of the time, it captured a widespread desire for unity and equality. At that moment, it resonated as both a reflection of existing tensions and a hopeful vision for the future.

“Everyday People” became Sly and the Family Stone’s first number one hit, selling over a million copies and solidifying their place in music history. It transcended genre and resonated across demographics, becoming a standard covered by a vast array of artists, from The Staple Singers and Ike & Tina Turner to Dolly Parton, Peggy Lee, and Pearl Jam. The song’s catchphrase, “different strokes for different folks,” entered the popular lexicon, further cementing its cultural impact.

Peak Fame and the Cracks Begin to Show

The period following “Everyday People” marked the peak of Sly and the Family Stone’s fame and influence. Their next album, Stand!, released in 1969, was another critical and commercial success. The title track, “Stand!”, became another hit single, and the album showcased the band’s continued musical innovation and social consciousness. “I Want to Take You Higher,” the B-side to “Stand!”, also became a popular song, further demonstrating their creative output.

Stand! became their most commercially successful album to date, achieving gold status within months and remaining on the charts for two years. It solidified their status as a major force in music, capable of blending artistic depth with mainstream appeal.

The summer of 1969 was a whirlwind of festival appearances, culminating in their iconic performance at Woodstock. Their sets at the Harlem Cultural Festival (featured in the documentary Summer of Soul) and the Newport Jazz Festival further cemented their reputation as electrifying live performers. At Woodstock, despite initial challenges with the late hour and a weary audience, Sly and the Family Stone delivered a legendary performance, captivating the massive crowd and solidifying their place in music history.

However, beneath the surface of their success, cracks were beginning to emerge. Interpersonal tensions within the band, fueled by romantic relationships and Sly’s increasingly erratic behavior, started to strain the group dynamic. Cocaine use escalated, particularly for Sly and Freddie, further exacerbating these issues.

Sly’s increasing control over the band’s creative direction also contributed to friction. He began to rely more on session musicians and multitracking, diminishing the collaborative nature of the Family Stone. The formation of Sly’s production company, Stone Flower, while intended to expand his creative output, further diverted his focus from the core band.

Descent and Legacy: There’s a Riot Goin’ On and Beyond

The shift in Sly’s creative process and the internal tensions within the band culminated in their 1971 album, There’s a Riot Goin’ On. This album marked a dramatic departure from the optimistic and celebratory tone of their earlier work. There’s a Riot Goin’ On is a dark, introspective, and often unsettling masterpiece, reflecting Sly’s deteriorating mental state and the turbulent social climate of the early 1970s.

The album’s sound is murky and lo-fi, a result of extensive overdubbing and tape degradation, mirroring the psychological disintegration Sly was experiencing. Tracks like “Family Affair,” while commercially successful and reaching number one, showcase a starkly different sound from their earlier hits. Recorded largely by Sly himself with minimal band involvement, “Family Affair” is a haunting and melancholic reflection on family dynamics, a far cry from the celebratory unity of “Everyday People.”

There’s a Riot Goin’ On is not a political album in the traditional sense, but it captures a profound sense of disillusionment and social unease. The album’s cover, a black, white, and green American flag, visually represents this subversion of national ideals. It is a deeply personal and idiosyncratic work, bordering on outsider art, and its influence can be heard in the music of Prince and countless artists who followed.

Following There’s a Riot Goin’ On, the original Sly and the Family Stone began to unravel. Larry Graham departed to form Graham Central Station, and Greg Errico left, replaced by Gerry Gibson and later Andy Newmark. Subsequent albums, Fresh (1973) and Small Talk (1974), showed further decline, both creatively and commercially.

The magic of Sly and the Family Stone, the unique blend of diverse personalities and musical talents that had created “Everyday People” and a string of groundbreaking hits, faded. Drug abuse, mental health struggles, and internal conflicts ultimately led to the band’s disintegration.

Despite their relatively short active period, Sly and the Family Stone’s legacy remains profound. They revolutionized American music, pioneering psychedelic soul and funk, and influencing generations of artists. “Everyday People” endures as an anthem of unity, a reminder of the power of music to bridge divides and celebrate our shared humanity. While Sly Stone’s personal struggles overshadowed the latter part of his career, the brilliance of his early work with the Family Stone, particularly songs like “Everyday People,” continues to inspire and resonate, a testament to their enduring impact on music and culture.