The Donner Family, also known as the Donner-Reed party, represents one of the most harrowing and tragic chapters in the history of American westward expansion. This group of pioneers, led by George Donner, became disastrously stranded in the Sierra Nevada mountains during the winter of 1846, leading to unimaginable suffering, starvation, and ultimately, acts of cannibalism. Their story serves as a stark reminder of the perils faced by those seeking a new life in the West and the desperate measures people will take to survive.

The dream of fertile land and opportunity in California spurred many families to undertake the arduous westward journey in the 1840s. In the spring of 1846, the Donner and Reed families, departing from Springfield, Illinois, joined this wave of westward migration. Initially comprised of about 31 individuals, including brothers George and Jacob Donner and businessman James Reed and their families, the group swelled as they progressed, picking up teamsters and employees along the way. By May, they had reached Independence, Missouri, and joined a larger wagon train heading west, full of hope and anticipation for their new lives.

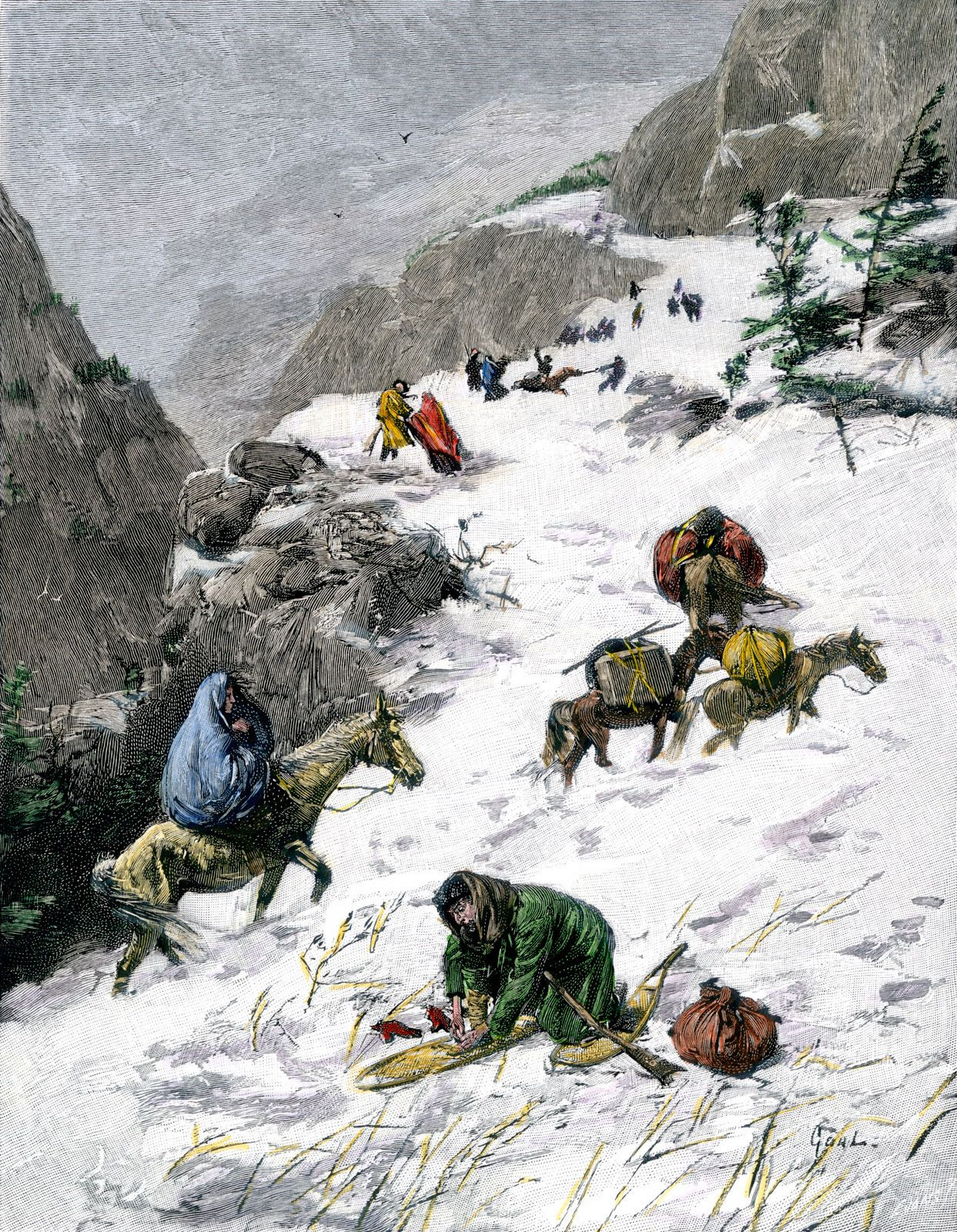

Illustration depicting the Donner Party struggling through the Sierra Nevada mountains in winter.

Illustration depicting the Donner Party struggling through the Sierra Nevada mountains in winter.

The journey began smoothly, and the Donner group made commendable progress, covering approximately 650 miles to Fort Laramie (present-day Wyoming) in just six weeks. However, at Fort Laramie, a fateful decision altered their course and sealed their tragic destiny. While the main wagon train opted for the well-established Oregon Trail heading north towards Fort Hall (Idaho), the Donner and Reed families, along with others, chose a supposed shortcut to California known as “Hastings Cutoff.” This route, promoted by an unreliable guide named Lansford Hastings, was deceptively marketed as a time-saver. Despite warnings from experienced travelers who had already traversed the treacherous “Hastings Cutoff” and cautioned against it, the group, under the newly elected leadership of George Donner, pressed forward, lured by the promise of a quicker path to California. At its peak, the Donner Family expedition consisted of 87 individuals – 29 men, 15 women, and 43 children – traveling in a column of 23 wagons pulled by oxen.

On July 31, the Donner Family entered Hastings Cutoff, a route intended to take them south of the Great Salt Lake in present-day Utah. Hastings had falsely claimed that this shortcut would shorten their journey by over 300 miles. In reality, Hastings Cutoff added a grueling 125 miles to their trek, leading them through some of the most unforgiving terrain in the Great Basin. Initially, progress was reasonable. However, Hastings, who had promised to guide the migrants, had departed with a different wagon company, leaving James Reed to navigate. As they forged a new path through the almost impassable Wasatch Mountains, precious time was lost. By August 30, after stocking up on water and provisions, they entered the Great Salt Lake Desert. Contrary to Hastings’ assurance of a two-day crossing, the desert traversal took five agonizing days. The Donner Family endured immense hardship, losing numerous cattle and abandoning wagons in the harsh desert environment. The search for lost oxen further depleted their dwindling time and resources before they embarked on a roundabout route through the Ruby Mountains in Nevada. By the time they finally rejoined the main California Trail at the Humboldt River, it was late September. The migrating season of 1846 was drawing to a close, and the Donner Family found themselves in a desperate race against time and the approaching winter to cross the Sierra Nevada mountain passes.

Adding to their woes, tensions within the exhausted group escalated. On October 5, a violent altercation between James Reed and a teamster culminated in Reed fatally stabbing the man. Although some advocated for hanging Reed, he was instead banished from the group. Reed continued westward alone on horseback, leaving his family to continue with the Donner Family party. As the migrants began ascending the Sierra foothills, their food supplies were critically low, and Paiute warriors further decimated their livestock by killing several oxen. By this stage, the desperate pioneers had cached almost all their possessions, burying them to lighten the load on their weary animals, retaining only essential food, clothing, and survival items. On October 31, the exhausted Donner Family reached the Sierra Nevada’s Donner Pass, only to find their path blocked by increasingly heavy snowfall.

With their westward progress completely halted by the relentless snow, most of the Donner Family constructed makeshift cabins near what is now Donner Lake. The Donner brothers’ families, delayed by a wagon accident, established their camp a few miles eastward near Alder Creek. Eight continuous days of heavy snowfall ensued, causing many of their remaining oxen, their primary food source, to wander off and become lost. On November 20, Patrick Breen, a member of the party, began a diary that would become the most important contemporary record of the Donner Family’s horrific winter ordeal. The first death in the camps occurred on December 15 when Baylis Williams, an employee of the Reed family, succumbed to malnutrition at the lake camp, foreshadowing the widespread death that was to follow.

Donner Pass and Donner Lake in California, a serene landscape that became a scene of unimaginable suffering for the Donner Party.

Donner Pass and Donner Lake in California, a serene landscape that became a scene of unimaginable suffering for the Donner Party.

On December 16, in a desperate attempt to find help, a group of 15 individuals, ten men and five women, set out to cross the mountains on crude snowshoes. Their journey was an unimaginable ordeal of cold, relentless storms, deep snow, and starvation. Eight of the men perished, and, in a horrific turn of events, some of their bodies were consumed by the survivors. Miraculously, two men and all the women managed to reach the Sacramento Valley, bringing news of the Donner Family’s plight. Californian settlers swiftly organized a relief party, which departed from Fort Sutter (Sacramento) on January 31, 1847. After a heroic struggle through deep snow, seven rescuers reached the lake camp on February 18. They evacuated 23 starving emigrants, primarily children, back to the settlements, though several perished during the arduous journey. Subsequent relief parties followed, but the severe conditions, illness, and injuries made it impossible to rescue everyone at once.

As dogs and animal hides were consumed, deaths mounted, and the unimaginable occurred: survivors resorted to cannibalism of the deceased to stay alive. The last survivor, Lewis Keseberg, who had sustained himself through cannibalism in the final weeks, was not rescued until April 21. In total, 42 members of the Donner Family perished: five before reaching the mountain camps, 34 at the camps or attempting to cross the mountains, and one shortly after reaching the settlements. Two men who joined the party at the lake also died. Forty-seven individuals survived the horrific ordeal.

The Donner Family tragedy vividly illustrated the immense dangers inherent in westward migration, yet it did little to deter the relentless flow of pioneers. Even survivors like Virginia Reed, despite recounting the unimaginable hardships in a letter to her cousin, advised future migrants to “never take no cutofs and hury along as fast as you can,” showcasing the enduring allure of California. The discovery of gold in California in 1848 triggered a massive gold rush, turning migration into a flood. The Donner Family’s story, while a grim and cautionary tale, became a footnote in the broader narrative of the westward expansion. Recent archaeological research at the Alder Creek campsite in 2010 failed to find physical evidence of cannibalism. However, researchers acknowledged that the absence of physical evidence does not negate the numerous contemporary accounts from rescuers and survivors confirming the occurrence of cannibalism. The Donner Family’s experience remains a chilling and unforgettable testament to human resilience and the depths of desperation in the face of unimaginable tragedy.