The landscape of organized crime in 20th-century America is inextricably linked to the rise of the Mafia, and within this shadowy world, the Luciano Crime Family stands as a towering force. Originating from the restructuring of New York City’s underworld by Salvatore Lucania, better known as Charles “Lucky” Luciano, this criminal syndicate evolved into what is now recognized as the Genovese crime family, one of the infamous Five Families. These families – Genovese, Gambino, Bonanno, Lucchese, and Colombo – carved up New York City’s criminal enterprises, forming a powerful and influential segment of the American Mafia, also known as La Cosa Nostra.

The formation of the Five Families was a direct consequence of the bloody Castellammarese War in the early 1930s. This conflict, named after the Sicilian origins of many involved, was a brutal power struggle that left dozens of mobsters dead. Emerging from this chaos, Lucky Luciano revolutionized the Mafia structure. He established The Commission, a governing body composed of bosses from the Five Families and other crime factions across the United States. This council was designed to prevent future wars, mediate disputes, and enforce order, effectively consolidating power within the hands of these select families. The Commission cemented the Five Families’ dominance in the American criminal underworld, granting them permanent seats at the table of organized crime leadership.

Luciano, already a dominant figure in lucrative criminal ventures such as extortion, prostitution, gambling, and bootlegging, was appointed head of one of these newly formed families. His trusted associate, Vito Genovese, was designated as underboss, second-in-command, of what quickly became the largest and arguably most influential of the Five Families. However, Luciano’s reign was cut short when he was imprisoned in 1936.

Frank Costello testifying before the Kefauver Committee in 1951, showcasing the scrutiny faced by organized crime.

Frank Costello testifying before the Kefauver Committee in 1951, showcasing the scrutiny faced by organized crime.

With Luciano behind bars, Vito Genovese stepped into the role of acting boss. However, facing potential prosecution for murder, Genovese fled to Italy in 1937. Despite his exile, Genovese maintained control, actively managing both legal and illegal businesses associated with the family. He cultivated relationships with the traditional Sicilian and Italian Mafia, models upon which the American Mafia had been structured, further solidifying his influence even from afar. In his absence, Frank Costello was appointed acting boss, maintaining the family’s operations.

Genovese’s ambition was far from quenched. By 1946, after witnesses in his potential murder case were eliminated, he returned to the United States a free man. His sights were set on seizing complete control of the Commission and establishing himself as the “boss of bosses.” Genovese orchestrated an assassination attempt on Costello, who, although surviving the attack, relinquished his position as family head. In 1957, Genovese was also implicated in the murder of Albert Anastasia, the leader of Murder, Inc., and a key ally of Costello.

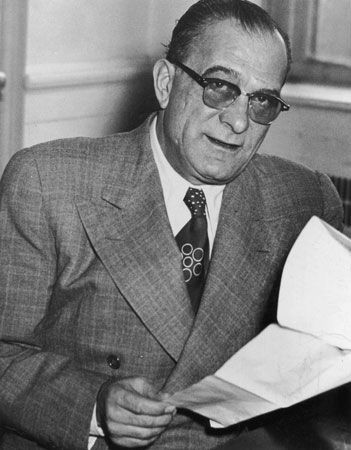

Vito Genovese, the boss who solidified the family's name and power, pictured in 1958 during his drug trafficking conviction.

Vito Genovese, the boss who solidified the family's name and power, pictured in 1958 during his drug trafficking conviction.

That same year, in a move that solidified his dominance, the family was officially renamed the Genovese crime family, honoring Vito Genovese’s ascent to power. Genovese then organized a national summit of Mafia leaders, the infamous Apalachin meeting in upstate New York. It is speculated that Genovese intended to use this gathering to solidify his coup. However, the meeting was raided by law enforcement on November 14, 1957. Nearly 100 mobsters were present, and approximately 60, including Genovese, were arrested. This raid inadvertently brought unprecedented federal scrutiny from the FBI onto the Mafia. Many within the organization blamed Genovese for this increased attention. Some theories suggest that Luciano, Costello, and Meyer Lansky, the Mafia’s financial mastermind, might have tipped off authorities to sabotage Genovese’s power grab, as none of them were present at the meeting. These figures may have also played a role in Genovese’s subsequent conviction on drug trafficking charges in 1959, further weakening his position.

Despite his imprisonment, Genovese’s control over the family remained considerable, though diminished. In 1962, Joe Valachi, a high-ranking member of Genovese’s organization incarcerated in the same prison, fearing for his life under Genovese’s paranoia, made a historic decision. Valachi became a government witness, publicly confirming the existence of the Mafia for the first time. His extensive testimony and subsequent memoir, encouraged by the U.S. Justice Department, exposed the inner workings of the mob and its hierarchical structure. This unprecedented breach of omertà, the Mafia’s code of silence, sent shockwaves through law enforcement and contributed to a shift in strategy. Coupled with the introduction of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act in 1970, the FBI’s intensified efforts significantly weakened organized crime in the latter part of the 20th century.

Vito Genovese remained the head of the family until his death from natural causes in prison in 1969. Following his death, the Genovese family experienced relatively stable leadership, albeit often through acting bosses while the official heads served prison sentences. Even into the 21st century, the Genovese family remains active, reportedly involved in white-collar crimes such as extortion, loan sharking, and gambling. Raids in 2006 led to the convictions of around 30 members on racketeering charges, and further arrests of alleged associates occurred as recently as 2022, demonstrating the enduring, albeit diminished, presence of the Luciano crime family’s legacy in the American underworld.