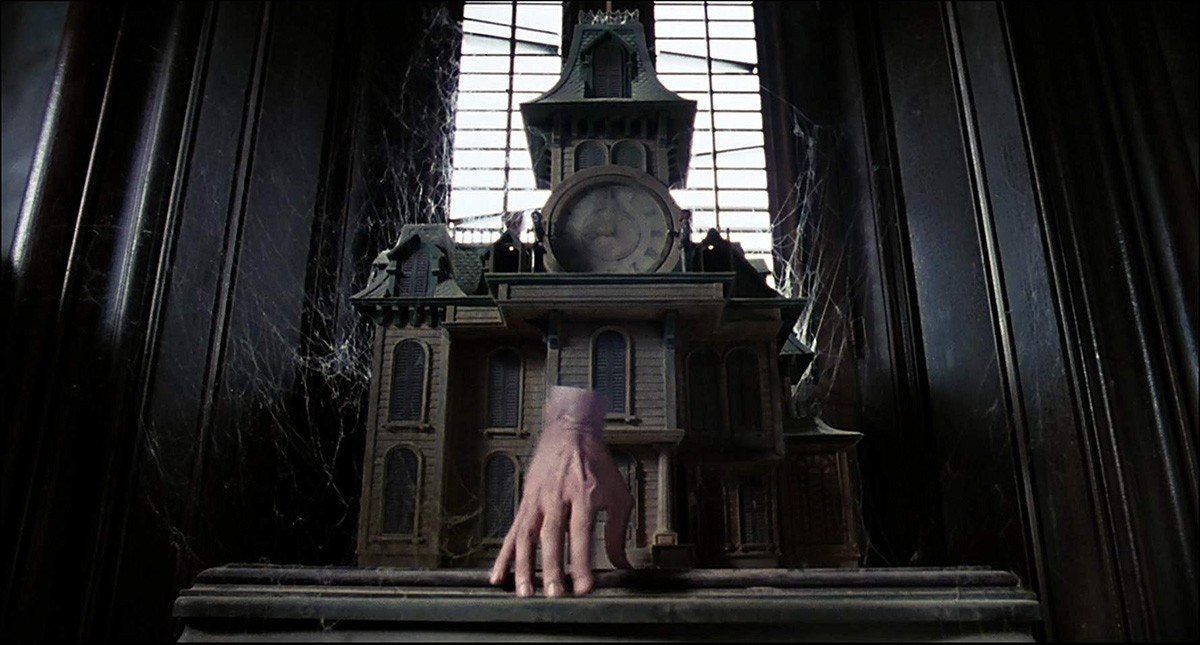

As a new animated rendition of The Addams Family prepares to grace cinema screens, courtesy of directors Conrad Vernon and Greg Tiernan, and Cinesite, it’s the perfect moment to delve into the legacy of this beloved franchise. Specifically, we’re turning our gaze back to the early 1990s when director Barry Sonnenfeld brought The Addams Family to life in live-action form. A standout challenge in the 1991 film, The Addams Family, was none other than Thing. This disembodied hand wasn’t just a prop; it was a character in its own right, requiring the ability to crawl, perform stunts, and ‘act’ convincingly in scenes. In an era preceding widespread CGI, the question was: how to make Thing a believable and captivating presence on screen?

Thing being directed on set

Thing being directed on set

To uncover the secrets behind Thing’s creation, we turn to Alan Munro, the visual effects supervisor for the 1991 Addams Family movie. Munro secured his role by suggesting a renowned dancer as inspiration for Thing’s movements and later championed the idea of using a real human performer. In his own words, get ready for a humorous and insightful breakdown of the process, from hand casting to minimal prosthetics and the painstaking art of rotoscoping.

Alan Munro: My journey with The Addams Family commenced in the summer of 1990, in Scott Rudin’s office. To be precise about the day? Let’s just say three decades and a bit of memory distortion might blur the details. I was there to interview with Scott Rudin and director Barry Sonnenfeld for the position of visual effects supervisor. The inevitable question arose: “How will you create Thing?”

My honest reply was, “I have no idea. And frankly, at this moment, I’m not concerned. First, we must define who Thing is and what his role is within the story. Once we understand that, the method of bringing him to life will become clear.”

“Alright,” they responded, intrigued, “Who is Thing?”

“In the script, Thing is portrayed almost as a family pet, a scurrying hamster-like presence. However, in my view, Thing needs to be more than that. He needs to possess a certain magic, an elegance – the grace of Fred Astaire.”

“Fred Astaire?” they questioned.

I elaborated, “Consider it. Astaire’s characters exist in a natural world, yet they transcend its limitations. His grace, his seamless movements, make the impossible seem effortless. When Fred Astaire dances on walls or ceilings, it feels completely natural. That’s the essence Thing should embody: natural yet unnatural, grounded yet unbound.”

And just like that, I landed the job.

Thing with Pugsley

Thing with Pugsley

While I might have contributed to Thing’s character, the visual conception of Thing is owed to production designer Richard MacDonald, and surprisingly, a children’s birthday party puppeteer.

For me, the vision for Thing’s appearance was straightforward. Aligning with the Fred Astaire inspiration, Thing should sport a crisp white French cuff, fastened with an Addams family crest cufflink. What about the wrist? That would remain unseen, shrouded in shadow within the deep cuff, adding to the mystique. Simple, elegant, and magical.

However, designer MacD (Barry’s moniker for MacDonald) was not convinced. “Thing wearing a cuff is absurd,” he retorted, “It’s like putting a hat on a hat.”

“No,” I corrected, “It’s like a cuff on a wrist. But, regardless, what’s your take on Thing’s appearance?”

“The inside of his wrist should resemble a teacup.”

“Huh?” I replied, genuinely perplexed. (And yes, this particular line of dialogue I recall verbatim.)

“Looking into an empty teacup,” MacD explained, “you lose sight of the bottom. There’s an illusion of infinite depth.”

Thing crawling

Thing crawling

MacD’s teacup analogy alluded to the smooth, porcelain slope creating an illusion of endless depth, perhaps if one were significantly inebriated.

He continued, “As Thing will be a puppet, this visual will be most effective.”

“Effective or not, Thing will not be a puppet,” I interjected. “Thing will be a real human hand, with the rest of the body optically removed.”

“No,” MacD insisted, “He’ll be a puppet. I’ve already found the puppeteer.”

“This, I have to witness.”

Christopher Hart as Thing

Christopher Hart as Thing

The following day, a charming gentleman in green-checkered trousers arrived, carrying a large orange checkered carpet bag. He opened the bag, produced a cassette player, and placed it on my desk. Next, he revealed two marionette control bars, each with numerous strings attached to an articulated wooden hand. For the next few minutes, the wooden hand elegantly waltzed to The Blue Danube on my office carpet. The hand indeed had a hollowed-out teacup wrist, designed to conceal the string attachments. Upon finishing his waltz, the puppeteer, with a thick Czech accent, inquired if I’d like to see a goat dance the polka. I politely declined. Before departing, he kindly crafted a balloon dachshund for me.

Fortunately, I had invited everyone – Barry, the director, and Scott, the producer – to witness this spectacle.

The verdict: Thing would indeed have a teacup wrist, but MacD would have no further say in the effects process. Sometimes, losing a minor battle leads to winning the overall war.

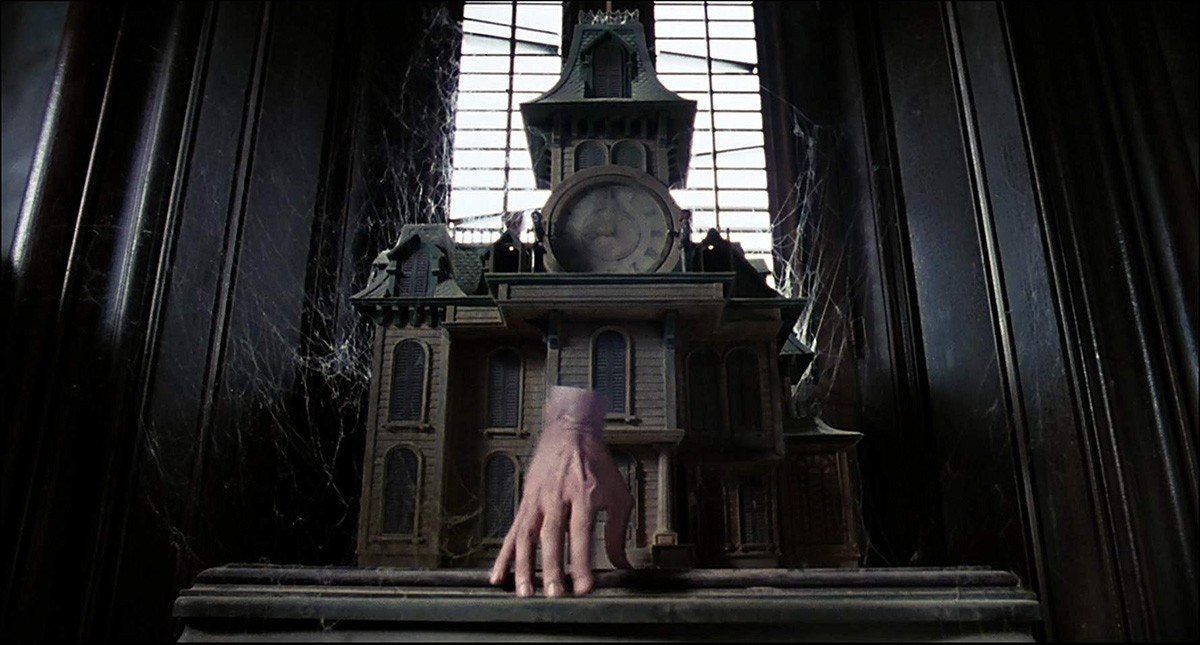

Thing playing chess

Thing playing chess

Next came casting. My initial choice for Thing was my friend, Don McLeod, a brilliant mime and Marcel Marceau’s apprentice. He was also known as the “American Tourister Gorilla” from those commercials where a gorilla, played by Don, attempted to break open suitcases. We conducted initial camera tests with Don, and while his performance was exceptional, his somewhat stubby hand didn’t quite fit the image. Fred Astaire’s moves require Fred Astaire’s graceful form. Don, unfortunately, didn’t quite fit the aesthetic.

I compiled a list of alternatives. Aside from mimes, magicians were the next logical choice – individuals trained in intricate hand movements. We issued a casting call to two dozen sleight-of-hand artists. The day they all responded was quite something. Never have I been asked for so many quarters, had so many playing cards divined, or had so many eggs produced from my ear. Ultimately, one candidate stood out.

Christopher Hart had been David Copperfield’s assistant and bore a striking resemblance to David, which had been utilized in several of Copperfield’s renowned illusions. Beyond his magic skills, Chris was tall, intelligent, athletic, and possessed wonderfully expressive hands. Moreover, Chris seemed relatively normal – a significant plus after spending an afternoon with two dozen magicians.

Christopher Hart, the actor behind Thing

Christopher Hart, the actor behind Thing

With our Thing cast, the next hurdle was achieving the effect. While it might seem straightforward now, remember this was before the dominance of computer-generated imagery. Everything had to be accomplished practically or using an optical printer.

I consulted Pete Kuran, a long-time collaborator. We decided on a two-pass shooting method: one with Chris performing as Thing and one clean background plate without him. Chris would wear various prosthetic wrist pieces. For front, top, and profile shots, Chris would lie face-down on a car mechanic’s dolly, arm extended, wearing a black sleeve. A prosthetic wrist, turned upwards, would create the illusion of a body positioned above. For shots from behind or when Thing needed to turn around, Chris would be positioned above the camera, with a prosthetic around his actual wrist to define the edge.

In post-production, Chris’s body would be removed through rotoscoping – a meticulous frame-by-frame animation process. Pete Kuran, having originated the Star Wars lightsaber effect, was Hollywood’s undisputed rotoscoping master. The clean background pass would then replace the areas where Chris had been removed, and the layers combined using an optical printer. A simple concept, yet incredibly complex in execution.

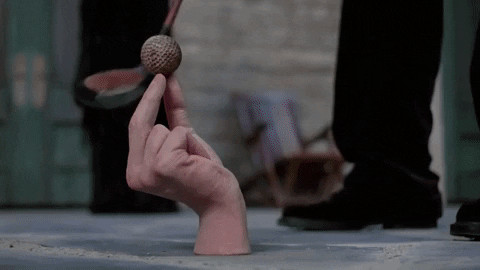

These optical shots featuring a real hand would be interspersed with shots of hand puppets – not marionettes, but mechanical hands covered in lifelike latex, designed for specific actions like Thing acting as a golf tee. For this, I enlisted Dave Miller, another collaborator from Nightmare on Elm Street.

This combination of techniques allowed us to keep the audience guessing, shot by shot, about the actual method behind the effect.

Dave Miller working on mechanical hand puppets for Thing

Dave Miller working on mechanical hand puppets for Thing

On the first day of filming, we positioned Chris under a table for the chess scene with Gomez. Camera stability was crucial for our two-pass technique. Unfortunately, the chess table was unsteady, causing endless wobbling. Stabilizing it became a lengthy ordeal, the set transformed into a web of guy-wires, and Barry almost reached his breaking point. Following that chaos, I was granted my own camera unit, essentially directing every shot of Thing in the film. This isn’t to claim Thing as solely my creation, overshadowing Barry Sonnenfeld, Chris Hart, Chuck Comisky, or the dozens of others involved. It was simply a matter of logistical organization.

Explore Alan Munro’s VFX credits on IMDB.