The Addams Family, with its macabre charm and darkly comedic sensibilities, has captivated audiences for generations. Among the eccentric members of this beloved family, Thing, the disembodied hand, stands out as one of the most peculiar and memorable characters. As a crucial part of the family dynamic, Thing’s on-screen presence in the 1991 film, The Addams Family, directed by Barry Sonnenfeld, presented a significant visual effects challenge. Before the widespread use of CGI, bringing Thing to life required ingenuity, practical effects, and a touch of old-school Hollywood magic.

To celebrate the enduring legacy of The Addams Family and its innovative effects, we delve into the behind-the-scenes story of how Thing was realized in the 1991 movie. Visual effects supervisor Alan Munro, in a conversation with befores & afters, recounted the fascinating journey of creating this iconic character, from conceptualization to execution. Munro’s approach, emphasizing character and performance over technology, ultimately led to a solution that was both practical and wonderfully bizarre.

When Munro was initially brought in to discuss the visual effects for The Addams Family, the creation of Thing was naturally a primary topic. During his meeting with director Barry Sonnenfeld and producer Scott Rudin, Munro candidly admitted he didn’t have a pre-conceived method for achieving the effect. Instead, he stressed the importance of defining Thing’s character and actions before figuring out the technicalities. This character-first approach resonated with the filmmakers.

Munro envisioned Thing as more than just a prop; he saw him as a character needing grace and personality. Famously, Munro pitched the idea of Thing embodying the elegance and seemingly effortless movement of Fred Astaire. He explained, “Think about it. Fred’s characters aren’t magical per se — they are grounded in the natural world. At the same time, they don’t seem bound by natural law. Fred is so graceful, so elegant, so effortless, so unbound, when he dances up the wall and onto the ceiling, it seems like the most natural thing in the world. That’s the quality Thing needs to have. Natural, yet unnatural. Bounded, yet unbound.” This artistic vision set the stage for how Thing would be brought to life, focusing on performance and subtle illusion.

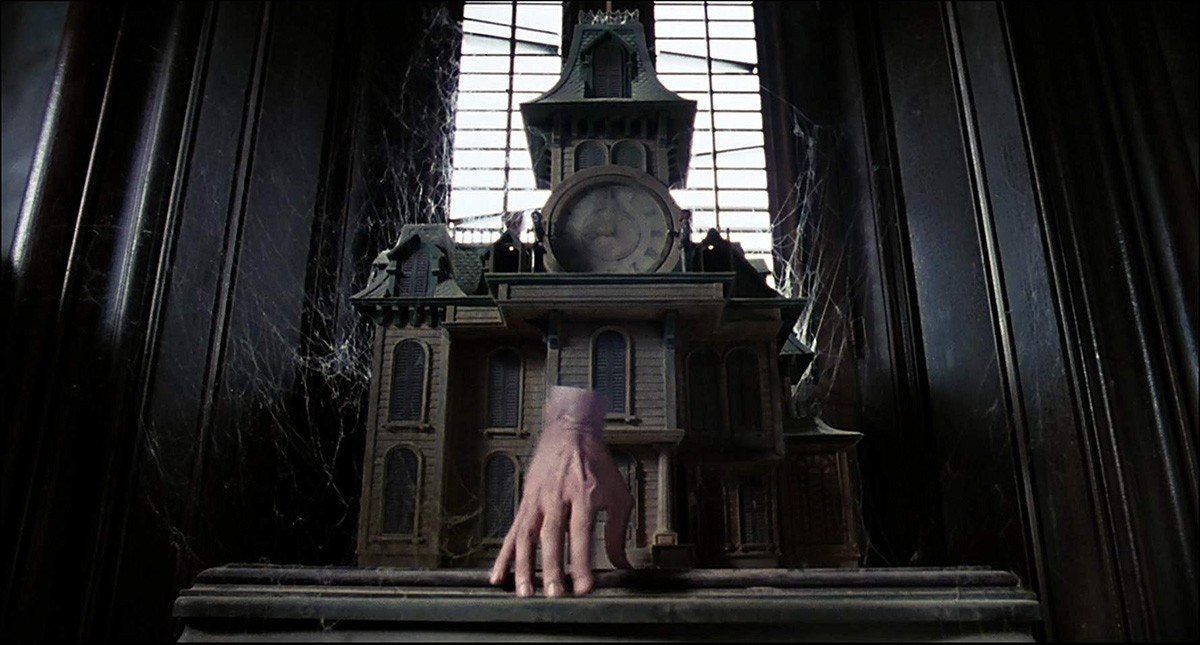

While Munro focused on the character’s essence, production designer Richard MacDonald contributed to Thing’s distinctive visual appearance. MacDonald proposed the idea of Thing having a “teacup wrist,” drawing inspiration from the illusion of depth created by the smooth, sloping interior of a teacup. This detail, initially met with amusement by Munro, became a key element of Thing’s design, adding to the character’s surreal and slightly unsettling aesthetic. Despite initial suggestions of using puppets, Munro firmly advocated for using a real human hand, believing it would bring a level of realism and nuance that a puppet could not replicate.

With the decision made to use a real hand, the next crucial step was casting the right performer. Munro initially considered Don McLeod, a mime known for his expressive physicality, particularly for portraying the “American Tourister Gorilla” in commercials. While McLeod’s performance was impressive, his hand’s physical appearance didn’t quite fit the envisioned aesthetic for Thing. The search then expanded to magicians, individuals skilled in sleight-of-hand and precise hand movements.

The casting call attracted numerous magicians, but Christopher Hart, a former assistant to David Copperfield, emerged as the ideal choice. Hart possessed not only exceptional dexterity and magical skills but also had large, expressive hands that were visually perfect for the role. Beyond his physical attributes, Hart’s professional demeanor and focus made him stand out. He brought the necessary combination of skill and sensibility to embody Thing.

The challenge then shifted to the technical execution of making a disembodied hand convincingly interact with the Addams Family. In the pre-digital effects era of the early 1990s, the filmmakers relied on practical techniques and optical printing. Munro collaborated with Pete Kuran, a visual effects expert renowned for his rotoscoping work, particularly on the Star Wars lightsaber effects. They devised a two-pass shooting method.

For each shot featuring Thing, two takes were filmed: one with Christopher Hart performing as Thing and another take of the empty scene without him. Hart would wear various prosthetic wrist pieces and perform from under tables, behind walls, or even suspended above the set, depending on the shot’s perspective. For shots where Thing was seen from the front or side, Hart would lie on a mechanic’s dolly with his arm extended, wearing a black sleeve that would be masked out later. For reverse angle shots, he would be positioned above the camera.

The magic happened in post-production through rotoscoping. Frame by frame, Hart’s body was painstakingly removed from the footage. The clean background plate, filmed without Hart, was then optically printed into the areas where he had been removed, creating the illusion of a disembodied hand. This meticulous process, while time-consuming, resulted in a remarkably seamless effect.

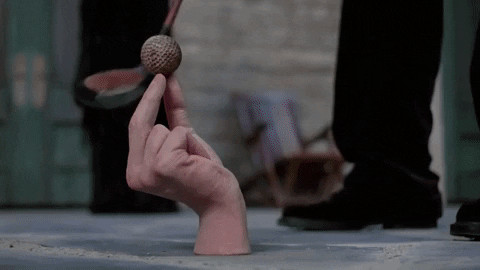

Complementing the live-action hand performances, mechanical hand puppets, crafted by Dave Miller, were used for specific actions that were too complex or impractical for a human hand. These lifelike latex puppets allowed for actions like Thing functioning as a golf tee or performing other specialized tasks. By intercutting shots of Hart’s hand and the mechanical puppets, the filmmakers kept the audience guessing about the techniques used, enhancing the character’s mystique.

Filming Thing wasn’t without its on-set challenges. Munro humorously recalled the first day of production where Thing was to play chess with Gomez Addams. The wobbly chess table became a major obstacle, requiring extensive stabilization to ensure the two-pass filming technique worked correctly. This incident led to Munro having his own dedicated camera unit to manage all of Thing’s shots, essentially making him the director for every scene involving the iconic hand. Despite the challenges, the collaborative spirit and ingenuity of the crew ultimately brought Thing to life in a way that remains iconic and fascinating to this day. The creation of Thing for The Addams Family stands as a testament to the power of practical effects and creative problem-solving in filmmaking, especially before the dominance of CGI.

The success of Thing in The Addams Family is a celebration of practical visual effects artistry. It highlights a time when filmmakers had to rely on clever techniques, performance, and meticulous craftsmanship to create fantastical characters. Thing remains an enduring symbol of The Addams Family‘s unique charm, and the story of its creation is a fascinating glimpse into the magic of movie-making ingenuity.