A jukebox, with the words

A jukebox, with the words

In the tapestry of rock and soul music history, few songs resonate with the enduring message of unity and acceptance as profoundly as “Everyday People” by Sly and the Family Stone. Released at a pivotal moment in the late 1960s, this track transcended musical boundaries, becoming an anthem for a generation grappling with social and racial divides. But “Everyday People” is more than just a catchy tune with a positive message; it’s a cornerstone in the story of Sly and the Family Stone, a band that itself embodied the very ideals of integration and musical innovation that the song championed. To truly understand the impact of “Everyday People,” one must delve into the journey of Sly and the Family Stone, a group whose groundbreaking sound and ethos redefined the landscape of American music.

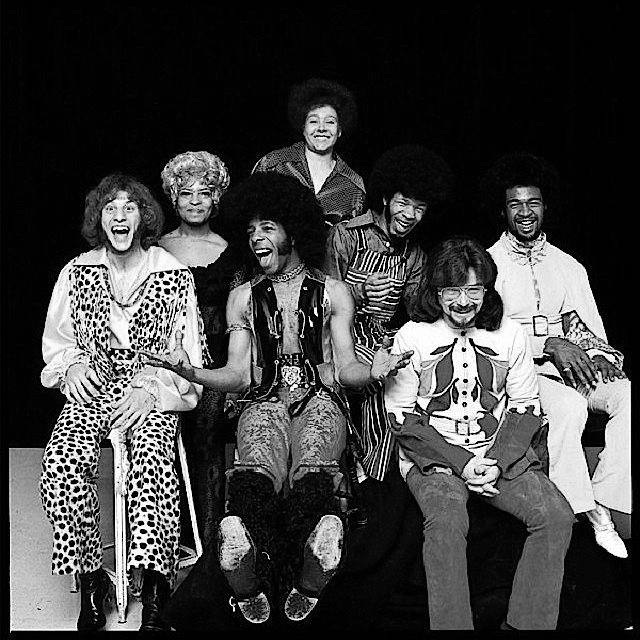

Sly and the Family Stone

Sly and the Family Stone

This exploration begins not with “Everyday People,” but with the diverse backgrounds and experiences that coalesced to form this revolutionary band. Before they became Sly and the Family Stone, the individual members were honing their skills in various corners of the music scene. Jerry Martini, the saxophonist, had cut his teeth in George and Teddy and the Condors, a band featuring Black singers backed by white musicians, navigating the complexities of racial dynamics within the music industry itself. This group, while not commercially explosive, offered Martini a taste of the big stage, including an appearance on Shindig! and even a brush with Beatlemania during a European tour. Leaving behind a lucrative residency at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas to join Sly’s nascent project, Martini’s decision was a testament to the magnetic pull of Sly Stone’s vision, even if it meant initial financial hardship and familial disapproval.

Greg Errico, the drummer, brought a different flavor to the mix, having previously played with a soul outfit known as the VIPs and then Freddie and the Stone Souls, led by Sly’s brother. While recordings of the VIPs remain elusive, Freddie and the Stone Souls, under Sly’s production guidance, had already begun experimenting with sounds that hinted at the Family Stone’s future direction, as evidenced by their instrumental track “LSD” from 1966. Cynthia Robinson, the trumpeter, added another layer of experience, having spent time in a bar band backing touring blues and R&B luminaries like Lowell Fulson, B.B. King, and Jimmy McCracklin.

However, none of these musicians possessed the same level of industry savvy and multifaceted musical background as Sylvester Stewart, the man who would become Sly Stone. Sly’s vision was born from a deep understanding of the evolving musical landscape and a keen awareness of the racial barriers that still persisted within it. As a radio DJ at an R&B station, Sly defied genre conventions by playing artists as diverse as Lord Buckley, The Beatles, Bob Dylan, and The Rolling Stones. This eclecticism, however, was met with resistance from some listeners who questioned the inclusion of “whitey” music on a Black radio station. Sly’s response was unequivocal: “there ain’t no Black and there ain’t no white and if it comes down to that there ain’t nobody Blacker than me. There ain’t nobody Blacker than Syl!”

This declaration encapsulated Sly’s artistic mission: to dismantle musical and racial boundaries and create a sound that resonated across demographics. He aimed to synthesize the melodic innovation of The Beatles, the lyrical depth of Dylan, and the raw funk of James Brown and Otis Redding. While precursors to this sonic fusion existed, they were fragmented. The Valentinos, Bobby Womack’s group under Sam Cooke’s wing, had flirted with the Beat group sound. The Chambers Brothers, a family band with a white drummer, transitioned from folk to rock. Love, in Los Angeles, with their interracial lineup, drew comparisons to Sly Stone, sharing similar personalities and career trajectories with Arthur Lee. The 5th Dimension, a Black vocal group known for their sunshine pop hits, also offered an influence, particularly in their vocal arrangements, which Sly would later acknowledge.

Yet, none of these contemporaries fully encompassed the ambitious scope of Sly and the Family Stone’s vision. Sly was aiming for a band that was not just Black or white, but both, incorporating female instrumentalists, blending vocal harmonies with rock instrumentation, and layering in horn sections and gospel-infused backing vocals. This was a radical concept, a deliberate dismantling of the segregated music scene.

In their nascent stages, Sly and the Family Stone’s live performances were rooted in familiar territory: Top 40 hits. The very first song they rehearsed was “I Don’t Need No Doctor,” a Ray Charles track penned by Ashford, Simpson, and Armistead. However, even within this cover-heavy repertoire, Sly’s philosophy of inclusivity and individual spotlighting was evident. “I wanted it to be able for everyone to get a chance to sweat,” he explained. “By that I mean… if there was anything to be happy about, then everybody’d be happy about it. If there was a lot of money to be made, for anyone to make a lot of money. If there were a lot of songs to sing, then everybody got to sing. That’s the way it is now. Then if we have something to suffer or a cross to bear — we bear it together.”

Their live show was meticulously designed to showcase each member’s individual talents. It began with a drum solo by Greg Errico, followed by a gradual onstage arrival of each band member, sometimes even emerging from the audience itself, each adding their instrument to the building instrumental piece, “The Riffs.” This opening number was a medley of jazz riffs in various keys and time signatures, a display of the band’s musical discipline and collective virtuosity.

The concerts were seamless, song flowing into song without interruption. Their early setlists featured covers tailored to highlight individual band members: Larry Graham tackling a Lou Rawls-esque “Tobacco Road,” Freddie Stone’s rendition of “Try a Little Tenderness” channeling Otis Redding, Cynthia Robinson’s bluesy trumpet take on “St James’ Infirmary,” and Jerry Martini’s sax-driven instrumental version of Junior Walker’s “Shotgun.”

Their initial residency was at The Winchester Cathedral, a venue owned by Beau Brummels’ former manager Rich Romanello. This club, primarily a haven for garage rock bands, became an incubator for Sly and the Family Stone’s burgeoning originality. Their growing popularity at The Winchester Cathedral empowered them to introduce original compositions into their sets.

Their first original song to make the setlist was “I Ain’t Got Nobody (For Real),” a track that vividly illustrates the collaborative nature of the band, moving beyond Sly Stone as a singular creative force. Sly’s original demo was a slow Latin jazz piece, a stark contrast to the band’s evolved rendition. In early 1967, the group recorded four demos, and though they didn’t settle the studio bill, these recordings would later surface on budget albums after their ascent to fame. Among these demos was a transformed version of “I Ain’t Got Nobody (For Real),” where the core melody and lyrics remained, but the overall feel was radically altered by the band’s collective input.

It was shortly after these demo recordings that David Kapralik entered the picture. Kapralik was an industry figure of contradictions. He described himself with a colorful phrase, “a middle-class New York-born humanist liberal Jewish prince,” and had previously held the position of head of A&R at the decidedly mainstream Columbia Records. During his tenure at Columbia, he signed mainstream artists like Andy Williams and Barbra Streisand, and even produced Muhammad Ali’s novelty album, “I Am the Greatest.” Yet, Kapralik also possessed a keen ear for innovation, having been instrumental in pairing Tom Wilson with Bob Dylan, a pivotal moment in rock history.

However, Kapralik’s career trajectory took a sharp turn due to John Hammond, the legendary talent scout. As Kapralik’s subordinate at Columbia, Hammond was, paradoxically, an industry giant in his own right, with a family lineage deeply embedded in the music business and a history of discovering iconic artists. Kapralik attempted to fire Hammond, allegedly due to complaints from Bob Dylan and Aretha Franklin about Hammond’s production. This claim, however, strains credibility, as neither Dylan nor Franklin were established stars at the time of their early collaborations with Hammond. Regardless of Kapralik’s true motivations, Hammond leveraged his industry connections, appealing directly to William Paley, the CEO of CBS, Columbia’s parent company. The result was Kapralik’s dismissal, not Hammond’s.

Kapralik transitioned into production and management, finding some success with Peaches & Herb. The duo’s biggest hits were still in the future, but their recent Top 10 hit, “Close Your Eyes,” bore Kapralik’s production credit. It was a San Francisco-based record promoter, Chuck Gregory, who steered Kapralik towards Sly and the Family Stone. Kapralik was instantly captivated. He was already familiar with Stone’s reputation as a producer, and Sly, in turn, knew of Kapralik’s executive background. A partnership was swiftly forged.

Kapralik’s relationship with Sly bordered on obsession. He became intensely invested in Sly’s approval, seemingly willing to compromise his own judgment and interests to align with Stone’s vision. This dynamic would become a recurring theme in Sly’s career, a pattern of individuals becoming deeply enmeshed in his orbit, often to their own detriment.

Kapralik secured the band a residency at the Pussycat A-Go-Go in Las Vegas, a relatively rare rock venue in a city dominated by more traditional entertainment. Gary Puckett and the Union Gap, and Ike and Tina Turner had also graced its stage. Sly and the Family Stone quickly became the must-see act in Vegas, drawing the attention of fellow entertainers. James Brown, The 5th Dimension, Nino Tempo, and Bobby Darin, a devoted fan, all frequented their shows.

However, the Vegas residency was abruptly cut short due to Sly’s interracial relationships. The Pussycat A-Go-Go’s owner, a man described as both a racist and connected to organized crime, took issue with Sly’s personal life, forcing the band to make a hasty exit from Las Vegas.

Prior to this incident, the band had already begun recording their debut album. While Kapralik had been ousted from Columbia, CBS Records had undergone a restructuring, with Clive Davis, a former lawyer, assuming the presidency of the newly rebranded label. Davis, reversing Kapralik’s earlier dismissal, rehired him as head of A&R for CBS’ subsidiary, Epic Records. Davis also permitted Kapralik to continue his management and publishing ventures independently, a testament to the industry’s then-lax approach to conflict of interest.

Around the same time, Davis experienced a conversion to the burgeoning countercultural rock movement after attending the Monterey Pop Festival at Lou Adler’s invitation. CBS, under Davis’s leadership, embarked on a concerted effort to sign San Francisco rock bands. This convergence of events led to Sly and the Family Stone signing with Epic Records shortly after aligning with Kapralik. During their Vegas residency, the band utilized their Mondays off to fly to Los Angeles, spend 24 hours in the studio, and then return to Vegas.

Their debut album’s opening track, “Underdog,” was another pre-Family Stone composition by Sly, originally recorded by The Beau Brummels, though their version remained unreleased. Sly’s revised rendition of “Underdog” was clearly aiming to capture the zeitgeist of summer 1967, even down to its intro. The Beatles had just released “All You Need is Love,” with its opening bars of the Marseillaise, and it seems likely this inspired Sly to begin “Underdog,” and indeed the entire album, with an excerpt from another traditional French melody.

Their debut album, A Whole New Thing, became an instant favorite among musicians, garnering praise from the likes of Mose Allison, Tony Bennett, and jazz legend Teo Macero. George Clinton of The Parliaments was reportedly astounded by “Underdog,” realizing the potential for new directions in his own music. The album also showcased the band’s democratic ethos, with both Larry and Freddie taking lead vocals, reinforcing Sly’s initial position as “first among equals.”

Despite critical acclaim and musician admiration, A Whole New Thing was a commercial failure. “Underdog,” the lead single, performed so poorly that its official release status remains debated, though photographic evidence suggests stock copies did exist beyond promotional releases. At this juncture, Sly Stone was a “musician’s musician,” lauded by his peers but unable to connect with a wider audience. His deep understanding of composition and music theory, applied to soul and rock, wasn’t yet translating into mainstream appeal. Rock critics, often out of sync with musical innovation, further hampered their initial reception. A Rolling Stone review dismissed the album as “more a production than a performance” and lacking in standout tracks, failing to recognize that A Whole New Thing was, in fact, the only Sly and the Family Stone album largely recorded live.

Undeterred by the initial commercial setback, CBS remained convinced of Sly and the Family Stone’s hit-making potential. Following the Vegas debacle, the band relocated to New York, securing a residency at the Electric Circus, a club with a storied past, having previously been the Balloon Farm and, before that, the Dom, the venue for the Velvet Underground and Nico’s early Exploding Plastic Inevitable shows. During this period, Rose Stone, Sly’s sister, joined the band on keyboards and vocals, becoming the fourth Stone sibling in the lineup and the second female instrumentalist. This completed the classic lineup that would achieve their greatest successes.

Rose’s arrival was pivotal. As Sly described, “Rose is the electric piano player, singer, dancer, and anything else I need… You see when Rose joined the group everybody was doing everything on stage, and that was almost a requirement that any new member had to meet.” She became a vital ingredient, but record sales remained elusive. Clive Davis and David Kapralik had a pivotal conversation with Sly, urging him to create something relatable, simple, and danceable for radio play. They suggested he could still pursue his experimental inclinations on album tracks, but for a single, they needed a pop song, reminiscent of his earlier dance-oriented productions.

Sly responded with “Dance to the Music.”

However, “Dance to the Music,” while commercially successful, was perceived by some within the band, particularly Jerry Martini, as a compromise of their artistic integrity. Martini, a foundational member of the group, viewed this shift towards commerciality with dismay. Decades later, Martini recounted, “Sly threw it down and he looked at me and said, “Okay, I’ll give them something.” And that is when he took off with his formula style. He hated it. He just did it to sell records. The whole album was called Dance to the Music, dance to the medley, dance to the shmedley. It was so unhip to us. The beats were glorified Motown beats. We had been doing something different, but these beats weren’t going over. So we did the formula thing. The rest is history and he continued his formula style.”

While the subsequent albums were undeniably more commercially oriented than their debut, labeling them as formulaic is a simplification. If a formula existed, it was one Sly and the Family Stone crafted themselves, a unique blend of innovation and accessibility. “Dance to the Music” certainly drew inspiration from existing sources. The line “Ride, Sally, ride” was a clear nod to “Mustang Sally.” The song’s structure, introducing each instrument sequentially, mirrored their live show introductions. It also bore a resemblance to King Curtis’s recent hit, “Memphis Soul Stew,” which employed a similar instrumental build-up.

Another element of the song’s genesis stemmed from an on-stage or rehearsal mishap – accounts vary. During a performance, Sly, forgetting the lyrics, filled in with “boom boom boom.” In subsequent repetitions of that section, Freddie and then Larry spontaneously joined in with the “boom boom” vocalization. These accidental “Boom boom booms” became a signature element of their live shows and were incorporated into the recording.

A final, serendipitous sonic element emerged from the practicalities of musician compensation. Union musicians received session fees for recordings, often a more reliable source of income than royalties in the 1960s. During an overdubbing session for the new album, Jerry Martini, whose saxophone parts were already recorded, attended the session to ensure his session fee. Not wanting to lug his saxophone unnecessarily, he brought a clarinet, an instrument with similar fingering but greater portability. While Martini was idly playing the clarinet in a back room, Sly decided its sound would be a perfect addition to the track. “Dance to the Music” thus became, to the best of our knowledge, the first soul hit to feature the clarinet as a lead instrument. Martini’s clarinet would become a recurring sonic signature in their subsequent releases.

“Dance to the Music” became a Top 10 hit in the spring of 1968, immediately impacting other musicians. Otis Williams of The Temptations, upon hearing Sly’s music, suggested to Norman Whitfield that this new sound was a direction worth exploring. Whitfield, initially dismissive, soon adopted this approach, leading The Temptations into the studio to record “Cloud Nine.” This track incorporated Sly’s social commentary, wah-wah guitar, call-and-response vocals, “boom-boom” backing vocals, and even a lyrical nod to The 5th Dimension (“up, up and away”), echoing Sly and the Family Stone’s earlier tribute.

This fusion of San Francisco hippie aesthetics and soul music, pioneered by Sly and the Family Stone and embraced by Whitfield, became known as “psychedelic soul.” It rapidly became the dominant sound in Black music for much of the following decade.

Their second album, named after their hit single, Dance to the Music, was a more cohesive work than their debut, focused on dance-oriented tracks like “Ride the Rhythm” and the twelve-minute medley “Dance to the Medley.” It also included “Higher,” Sly’s first reimagining of “Advice,” a song he had previously written for Billy Preston. In a characteristic nod to musical lineage, “Higher” now incorporated an intro that bore a striking resemblance to Jackie Wilson’s hit, “(Your Love Keeps Lifting Me) Higher and Higher.” The version of “Higher” on Dance to the Music would not be the last time the band revisited this song.

Despite the commercial success of the title track single and its deliberate commercial appeal, the Dance to the Music album fared only marginally better than its predecessor, reaching number eleven on the R&B albums chart but only number 142 on the pop charts. However, the single “Dance to the Music” was a significant hit, enabling them to indulge in playful ventures like recording a French-language parody, released under the moniker The French Fries, titled “Dance a La Musique.”

The Dance to the Music album was recorded in New York, and during their time there, the band’s internal dynamics began to shift. A pivotal moment occurred during their first performance at the Fillmore East in May 1968, where they opened for the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Normally, the Fillmore East featured a three-act bill, but Sly and the Family Stone and the Experience were considered such powerful live draws that Bill Graham deemed a third act unnecessary.

According to David Kapralik, this Fillmore East performance marked a turning point. “Up to that point, each individual member had their star piece. Each member did a solo. At the Fillmore, he decided that it was going to be a one-man show and everybody else was going to back him up, and he took away all their solos. That was the first change of substance that I saw.” While not an immediate and complete transformation – a later Fillmore East live album still features Cynthia Robinson’s trumpet solo on “St. James Infirmary” – from this point onwards, Sly increasingly became the central focus onstage. The emphasis shifted subtly from Sly and THE FAMILY STONE to SLY and the Family Stone.

Despite this internal shift, the Fillmore East gig was a resounding success. Knowing they had to impress a Hendrix-centric audience, they put on an extraordinary show. At one point, Sly, Freddie, and Larry jumped into the audience, passing the bass to Cynthia (despite her not being a bass player), and launched into “Hambone,” the body percussion and dance tradition, leading the audience out of the theatre and back in again, all while maintaining the rhythm with Cynthia and Greg Errico holding down the beat.

That Fillmore East night also marked another, more concerning shift. According to Jerry Martini, it was the first time he witnessed Freddie Stone using cocaine. New York City became the backdrop for cocaine’s increasing presence in the band’s life. Cocaine, largely absent from the earlier rock and roll narrative, was about to become a pervasive force in the music world. While heroin dominated the jazz scene and amphetamines fueled long club gigs in previous decades, and psychedelics expanded minds, cocaine’s ascendance was imminent.

Cocaine’s rise in the counterculture accelerated around 1969, coinciding with the release of Easy Rider. However, Sly Stone was ahead of this curve, having experimented with the drug in 1967 and becoming a heavy user by 1968. Cocaine’s impact would become a central, and often destructive, element in the Sly and the Family Stone story.

Cocaine’s effects stem from its disruption of dopamine reuptake in the brain. Dopamine, a neurotransmitter, is central to the brain’s reward system, associated with pleasure and motivation. Cocaine blocks the reuptake process, leading to an excess of dopamine in the synapse, creating intense euphoria, heightened energy, suppressed appetite, and an inflated sense of well-being. However, this dopamine overload can also lead to negative consequences: psychosis, hallucinations, mood swings, and paranoia. Paradoxically, cocaine’s impact on the limbic system, the brain’s emotional and memory center, reinforces the craving for more cocaine, creating a cycle of dependence. Furthermore, prolonged cocaine use can rewire the brain’s stress response, making users more susceptible to anxiety and stress when not under its influence.

These effects began to manifest in the behavior of Sly and the Family Stone members, most notably Sly himself. The follow-up single to “Dance to the Music,” “Life,” failed to chart in the US, though its B-side, “M’Lady,” surprisingly reached the lower rungs of the UK Top 40. To promote these singles, and capitalize on the success of “Dance to the Music,” the band embarked on a UK tour. Jerry Martini had planned to dispose of a joint before boarding the plane, but Larry Graham intervened, suggesting Martini give it to him instead. Upon arrival in the UK, Graham, being Black and thus more likely to be targeted by customs, was searched and arrested.

Further complications ensued in the UK. The band’s equipment was delayed in transit, forcing them to rely on rented gear provided by the promoter, Don Arden. Arden, notorious for his disregard for artistic integrity and his reliance on intimidation tactics, supplied substandard equipment. At their first promotional gig, the Hammond organ provided was riddled with malfunctioning keys. The band refused to perform under these conditions, prompting Arden to issue veiled threats. Ultimately, they took the stage, but instead of playing, Sly addressed the audience, explaining the equipment issues and their unwillingness to deliver a subpar performance. He engaged with audience members, turning a potential disaster into a unique, albeit equipment-challenged, experience.

“Life,” the song whose B-side was “M’Lady,” was also the title track of their third album, released less than a year after their debut. Life, the album, marked a deliberate shift away from the pure party vibe of Dance to the Music, leaning back towards experimentation and targeting the burgeoning hippie rock audience. This shift was sometimes explicit, as in “Plastic Jim,” which borrowed elements from The Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby” and The Mothers of Invention’s “Plastic People.” The Mothers of Invention, with their sonic experimentation and socially conscious, sometimes satirical, lyrics, were perhaps the closest contemporary to the Life era Sly and the Family Stone. Tracks like “Jane is a Groupee,” with its fuzz guitar and misogynistic lyrics about uninformed groupies, could have easily found a place on a Zappa album.

While the horn-driven sound now firmly associated with soul music was becoming increasingly prominent in rock, with bands like The Buckinghams and Blood, Sweat & Tears incorporating horns, Life was consciously geared towards the white rock market. However, the white rock market remained largely indifferent. Neither the singles nor the album achieved commercial success. Sly and the Family Stone appeared to be in danger of becoming a one-hit wonder.

However, the enduring popularity of “Dance to the Music” led to a crucial appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. Their performance featured a dynamic medley of “Dance to the Music,” “Music Lover,” and “I Want to Take You Higher,” including a segment where Sly and Rose ventured into the audience, encouraging singalongs and good times. Sly even reprised his “Hambone” dance from the Fillmore East. The Ed Sullivan Show audience, predominantly white and older than the band’s target demographic, appeared largely unmoved by the audience participation segment. At the medley’s conclusion, Sly’s parting words, “Thank you for letting us be ourselves,” foreshadowed the title of a future hit. But the most significant moment in this performance was the debut of a snippet of a new song: “Everyday People.”

“Everyday People” was meticulously crafted for mass appeal, and it succeeded spectacularly. Built around Larry Graham’s distinctive slap bass, which plays a single low G throughout the entire song, and utilizing only two chords, the melody was deceptively simple, almost a playground chant. Yet, the song was layered with hooks: the horn line, the “I am everyday people” chorus, and the “We got to live together” counter-vocal. Its hook density rivaled even bubblegum pop hits like “Sugar, Sugar.”

Sly later stated his ambition for “Everyday People”: “I didn’t just want “Everyday People” to be a song. I wanted it to be a standard, something that would be up there with “Jingle Bells” or “Moon River.” And I knew how to do it. It meant a simple melody with a simple arrangement to match. I think Larry played a single note through the whole song.”

The song’s message was equally straightforward, yet deeply resonant with the socio-political climate of the time. The final verse addressed racial intolerance directly. Consistent with the band’s ethos of racial integration, the song offered an optimistic perspective on race relations, reflecting the hopeful atmosphere of the late 1960s. Following the Voting Rights Act, Loving v. Virginia, and the Civil Rights Act, it seemed to many that institutional racism was being dismantled, paving the way for a level playing field. The remaining challenges, it was believed, were personal prejudices rather than systemic inequalities. Black and white could coexist, the song suggested, through acceptance of differences and equal opportunity.

Sly articulated his philosophy at the time: “You can’t scream that because you are a color you are anything. You are black — you are black, that’s all. You are among people who’ve been mistreated a lot. But it doesn’t necessarily mean that a white person next door is responsible. His grandfather may have killed your grandfather, but he himself may love you. It’s simple. Either everything’s fair or nothing’s fair. Either everybody gets a chance to do what he wants or… you know what I mean?”

This viewpoint, while perhaps naive in retrospect, was a widely held and defensible position in the late 1960s. Sly extended this message of universality beyond race, appealing to their hippie fanbase with a verse about judging individuals based on appearance. In the late 1960s, hippies were often seen as natural allies of the Civil Rights movement, with the anti-war movement emerging from and adopting the structures of the earlier Civil Rights activism. Both Black people and hippies faced societal backlash from conservative elements.

However, the comparison between racial discrimination and discrimination based on appearance glossed over a critical distinction: race is immutable, while hairstyle is a choice. As the draft threat receded in the early 1970s, hippie radicalism waned. Released in November 1968, shortly before Nixon’s election signaled a shift towards the “Southern Strategy,” “Everyday People,” while capturing the tensions of the era, also presented a somewhat idealized vision of the future. Yet, in that brief moment, it served as both a reflection of societal realities and an aspirational anthem.

“Everyday People” soared to number one, holding the top spot for a month and selling over a million copies. Billboard ranked it as the fifth biggest hit of 1969. Sly’s ambition for the song to become a standard was realized. It was covered by a diverse range of artists, from The Staple Singers, The Four Tops, and The Supremes, to Ike and Tina Turner with the Ikettes, Dolly Parton, The Four Freshmen, Belle and Sebastian, and Pearl Jam. Peggy Lee’s cover, recorded as the original climbed the charts, stands out as a particularly intriguing interpretation.

“Everyday People” achieved a cultural penetration akin to “Respect,” popularizing the phrase “different strokes for different folks,” which transitioned from a Muhammad Ali quote to a ubiquitous idiom.

The B-side, “Sing a Simple Song,” also charted, reaching the Top 30 on the R&B charts and the lower reaches of the Hot 100. Their next single, “Stand!,” the title track of their upcoming album, reached number 22. “Stand!” marked a departure in the band’s creative process, becoming the first track not entirely created by the group itself. Sly, dissatisfied with the initial version, brought in session musicians to record a new tag, which many consider the song’s highlight. At this peak of his songwriting and arranging prowess, Sly was firmly in control in the studio, providing sheet music to the session musicians, a departure from the head arrangements common in rock and soul production.

The B-side of “Stand!,” “I Want to Take You Higher,” was a reworking of “Higher,” itself a reimagining of “Advice.” Third time proved to be the charm. Despite being a B-side, “I Want to Take You Higher” reached the Top 40, fueled by its “Boom lakalakalaka” vocals and a nod to the hippie audience with a reference to a Doors hit. “I Want to Take You Higher” became another widely covered song, including a Top 40 version by Ike and Tina Turner.

Stand!, their fourth album in eighteen months, showcased their prolific output. While the instrumental jam “Sex Machine” stretched to an indulgent fourteen minutes, the album’s strength was undeniable. Five of its seven other tracks would later be included on their Greatest Hits collection, underscoring its overall quality. The album, while commercially potent, also explored more socially conscious themes, sometimes with a sharper edge than “Everyday People,” as evidenced by the provocative “Don’t Call Me N—-r, Whitey.”

The NME review lauded the album as showcasing “the hard rock group which weaves not only exciting instrumental patterns but vocal ones as well.” Stand! reached number thirteen on the album charts, remaining charted for two years and achieving gold status within months, a significant leap from their previous albums.

However, this breakneck pace of album releases – four in eighteen months – would soon slow dramatically. It would be over two years before their next album of new material. The summer of 1969 was dominated by festivals for Sly and the Family Stone, their presence on diverse lineups reflecting the evolving musical landscape. They shared stages with Chuck Berry, Dr. John, The Band, The Velvet Underground, The Bonzo Dog Band, Procol Harum, Blood Sweat and Tears, Tiny Tim, The Mothers of Invention, Johnny Winter, and The Jeff Beck Group.

Three festivals in particular stood out: The Harlem Cultural Festival, The Newport Jazz Festival, and Woodstock. The Harlem Cultural Festival, later dubbed “Black Woodstock,” was a series of free concerts in Harlem aimed at community cohesion and preventing summer race riots. Sly and the Family Stone headlined the first show, with security provided by the Black Panthers due to police reluctance. The Black Panthers ensured a safe environment for the event.

The Newport Jazz Festival in 1969 was notable for its inclusion of rock acts alongside jazz legends. The lineup included Buddy Rich, Art Blakey, Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck, Sun Ra, The Mothers of Invention, James Brown, The Jeff Beck Group, Jethro Tull, and the then-new Led Zeppelin. Sly and the Family Stone’s performance at Newport is often cited as the catalyst for a riot. Hundreds broke down fences to gain free entry, leading to a chaotic influx of people into the already packed venue and a police response with riot shields.

Between these festivals, Sly and the Family Stone also played a series of dates at the Harlem Apollo, seeking to reconnect with their Black audience and address concerns about their primarily white rock fanbase. During one Apollo performance, Jerry Martini, the white saxophonist, was initially met with boos from the audience. Sly had to address the crowd, emphasizing the band’s integrated nature and Martini’s musical talent. A woman in the audience defused the tension with a shout, and the white band members felt accepted at the Apollo from that point on.

At the end of July 1969, coinciding with the Apollo dates and the moon landing, they released “Hot Fun in the Summertime,” another iconic single. It reached number two on the charts, becoming a summer anthem. The song at number one while “Hot Fun in the Summertime” was at number two was The Temptations’ “I Can’t Get Next to You,” Norman Whitfield’s latest Sly and the Family Stone imitation, highlighting Sly’s pervasive influence on the musical landscape.

Then came Woodstock. Initially, the band struggled to connect with the exhausted, late-night Woodstock audience. Equipment problems further disrupted their set. However, after a couple of opening songs, they launched into a twenty-minute medley of their hits, culminating in audience participation and a triumphant set. Rolling Stone’s review of Woodstock hailed Sly and the Family Stone as the standout act, surpassing even major headliners.

Woodstock arguably marked the zenith of Sly and the Family Stone’s career. However, the seeds of their decline were already sown. Interpersonal tensions within the band, fueled by romantic entanglements and Sly’s increasingly erratic behavior, began to surface. Larry Graham and Rose Stone’s relationship was strained by Sly’s gangster friend, Bubba Banks, who pursued Rose. Sly himself was involved with Cynthia Robinson and multiple other women. Sly’s sister Loretta, uninvolved in the band’s performance aspect, exerted influence on the business side, advocating for Kapralik’s removal, supported by Sly’s new associates who also pushed for the removal of the white band members. While Sly resisted these pressures, relationships within the band frayed.

Relocating to Los Angeles, the entertainment industry hub and also the center of the cocaine trade, exacerbated the situation. Cocaine use became a significant problem, particularly for Sly and Freddie, who grew closer but increasingly distanced from the rest of the band.

Kapralik established Stone Flower, a production company for Sly to produce other artists, distributed by Atlantic. Stone Flower released four singles, including two Top 40 hits for Little Sister in 1970, “You’re The One” and “Somebody’s Watching You,” a remake of the Stand! track.

The Greatest Hits compilation released in 1970 was a stopgap measure during this period of creative stagnation. Between September 1967 and April 1969, they had released four albums. In the remaining months of 1969, they released two non-album singles, “Hot Fun in the Summertime” and “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin).” “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” was partly a self-celebration, namechecking their hits, but also hinted at a growing paranoia. It became their second number one single, and the last to feature the classic lineup and the last new recording for nearly two years.

Sly was grappling with creative blocks, searching for a new direction, hampered by cocaine addiction. He began to favor multitracking recordings himself, reducing band involvement. Little Sister’s “Somebody’s Watching You” reportedly became the first Top 40 hit to utilize a drum machine, reflecting Sly’s increasing reliance on studio technology and isolation. He moved into a mansion previously owned by John and Michelle Phillips, equipped with a hidden sixteen-track recording studio. While band members sometimes resided there, Sly’s behavior grew increasingly erratic and stressful.

Sly’s collaborations during this period often involved musicians known for both their talent and their shared cocaine use, including Miles Davis and Johnny “Guitar” Watson, though neither definitively appeared on Sly’s recordings from this time. Terry Melcher, a controversial figure, became a close associate. Bobby Womack and Ike Turner also became part of Sly’s inner circle. Sly reconnected with Billy Preston, co-writing an instrumental B-side for Preston, “As I Get Older,” produced by Ray Charles.

Touring continued, but increasingly plagued by Sly’s unreliability. Sly and Freddie routinely arrived hours late for gigs, or not at all, citing a desire to build audience anticipation, but in reality, engaging in drug use. Approximately one-third of their scheduled shows were cancelled. Jerry Martini recounted a Chicago concert where, he claimed, Mayor Richard J. Daley orchestrated a riot by deliberately delaying the band’s arrival announcement to incite the crowd and blame the band.

David Kapralik, Sly’s manager, succumbed to Sly’s influence and cocaine use. Kapralik later described his experience: “I was blown away on cocaine. Sly would sit, imperially and imperiously, with lines in front of him, white lines and a line of people with their nostrils extended out to the spoon that he was offering. I was right there in the line, I admit… All the pain I was in, all the pain around me. My vision had disintegrated by this point. Sly’s productivity was suffering, to put it mildly. I had no influence over what Sly was doing. I never had control. I never tried to have control. I had influence over Sly. I was managing the unmanageable. I influenced.”

Kapralik, overwhelmed, eventually relinquished management to Ken Roberts. Around the same time, Larry Graham departed the band after Rose Stone left him for Bubba Banks. Graham formed Graham Central Station, achieving R&B and pop success.

Sly continued working on an album initially titled Africa Talks To You, eventually released as There’s A Riot Goin’ On. Greg Errico was the first to leave during the sessions, citing the increasingly toxic environment. He was replaced by Gerry Gibson, a session drummer previously known for his work with The Banana Splits. Martini and others considered Gibson a lesser drummer. Gibson’s audition involved playing to a drum machine track for “(You Caught Me) Smilin’,” which became the final recorded take.

There’s A Riot Goin’ On was largely constructed from overdubs and retakes, a departure from their previous live-in-the-studio approach. Larry Graham reported never playing simultaneously with other band members during the sessions. The album’s murky sound resulted from both stylistic choice and the degradation of tapes through repeated recording and erasure.

The lead single, “Family Affair,” featured Sly on most instruments, with Rose on vocals, Bobby Womack on guitar, and Billy Preston on electric piano, but none of the core band members except Sly and Rose. Despite its unconventional and dark sound, “Family Affair” and There’s A Riot Goin’ On both reached number one. “Family Affair” became their last number one single.

There’s A Riot Goin’ On is often perceived as a socially conscious album, largely due to its title and the black American flag cover. However, it is more accurately a portrayal of a mind in breakdown, a dark and oppressive record. It is considered a masterpiece of lo-fi aesthetics, influencing Black music for decades to come, most notably Prince.

Those around Sly began to perceive him as two distinct personas: Sylvester Stewart, the creative genius, and Sly Stone, the self-destructive figure. Kapralik, in his own downward spiral, described his relationship with Sly as “unbearable.”

Kapralik stepped down from management, remaining involved in publishing and production. Around the same time, the band’s rhythm section changed, with Gibson replaced by Andy Newmark and Larry Graham departing. Graham’s bass work remained on two Fresh album tracks, including a cover of “Que Sera Sera,” allegedly included after Sly met Doris Day and performed the song for her.

Graham formed Graham Central Station, while Sly and the Family Stone continued with a new bassist, Rusty Allen, and a second saxophonist, Pat Rizzo. Fresh reached the Top 10, featuring their last Top 20 hit, “If You Want Me To Stay.”

Sly’s personal life became increasingly tumultuous. His marriage to the mother of his child, a publicity stunt wedding at Madison Square Garden, quickly dissolved. By 1974, with the release of Small Talk, considered their first weak album, the original Sly and the Family Stone was effectively over. A Radio City Music Hall residency drew minuscule crowds. Freddie Stone described the experience as tasteless and empty, signaling the band’s disintegration. Sly essentially ceased communication and invitations to gigs, and the band members largely moved on.

Sly released a solo album in 1975, followed by albums under the Sly and the Family Stone name with ersatz lineups. Cynthia Robinson remained loyal, continuing to collaborate sporadically with Sly. Cynthia briefly joined Graham Central Station and also worked with Prince and George Clinton. Freddie Stone became a pastor. Rose Stone pursued a solo career and became a backing vocalist for various artists. Sly cycled through periods of sobriety and relapse, and legal battles over finances.

A brief 2006 Grammy reunion, minus Graham, was marred by Sly’s erratic performance. Attempts at a full reunion failed. However, Cynthia, Jerry, and Greg formed a new lineup, Family Stone, with Sly’s daughter Phunne on vocals, touring and releasing a single in 2015. Cynthia Robinson passed away shortly after. Phunne and Jerry continue to tour as Family Stone.

Sly released a final album in 2011, a collection of remakes, met with little success. He faced financial hardship, living in a mobile home. Recent years have seen sporadic comeback attempts, collaborations, and a ghostwritten autobiography. He reportedly won back some of his lost finances and has a house again. He released a Christmas single in 2023. While health issues prevent touring, he is reportedly content, spending time with his children and grandchildren.

Sly and the Family Stone’s meteoric career was cut short by internal strife and self-destruction. Yet, their musical legacy remains immense. They revolutionized rock, pop, soul, and funk, influencing generations of artists, from Prince and Michael Jackson to Talking Heads and Red Hot Chili Peppers. Despite his fall from grace, Sly Stone’s impact on music remains undeniable, forever taking music “higher.”