Delving into the appendices of The Lord of the Rings often reveals fascinating details that enrich our understanding of Tolkien’s intricate world. Recently, while exploring the Dwarvish genealogy, a seemingly minor detail regarding Durin VII caught my attention. This small point, upon closer examination, unfolds into a complex tapestry of questions about Dwarvish history, prophecy, and the very nature of Durin’s lineage.

The figure of Durin VII raises several intriguing questions. When was Durin VII born? What era did he reign in? And perhaps most importantly, what is the significance of the epithet “the Last”?

From Tolkien’s perspective as the author, these questions might appear straightforward. Durin VII is presented as a descendant of Thorin III, placing him in the timeline after the establishment of the Fourth Age. This is based on Tolkien’s established lore.

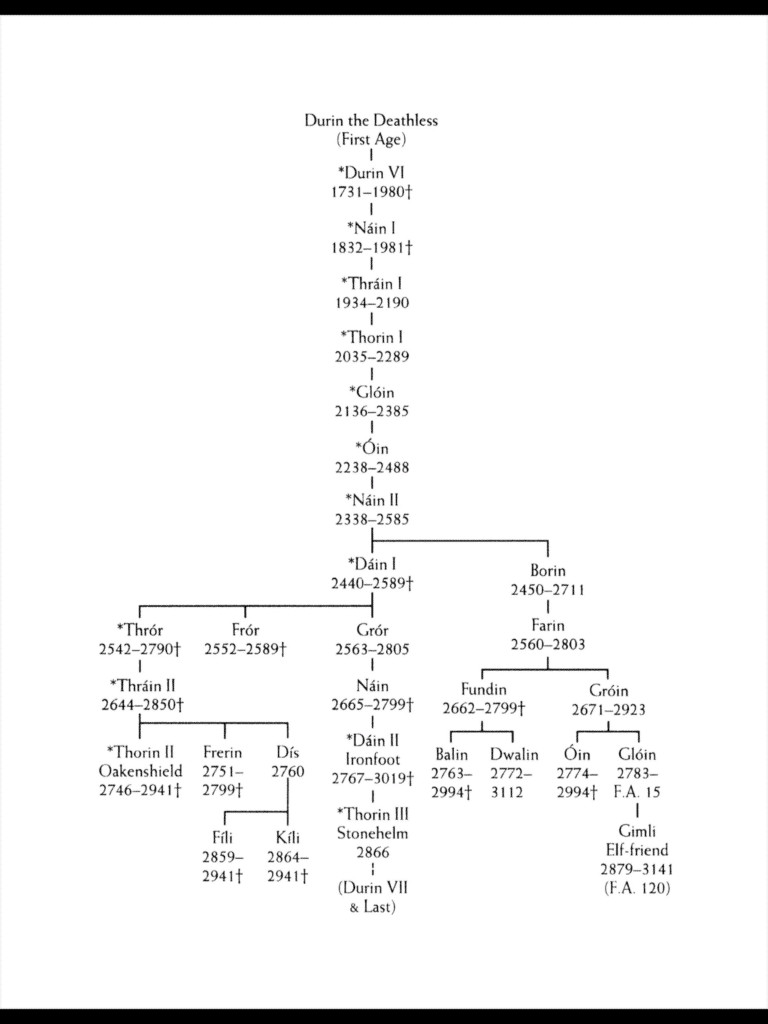

However, considering Tolkien as a translator and scholar of ancient texts, as he often framed himself, these questions become more complex. The genealogical table in the appendices, seemingly compiled at the end of Aragorn’s reign, doesn’t explicitly include Durin VII’s birth. This absence begs the question: how can Durin VII be listed as a Dwarvish King if he wasn’t even born by the time the record was ostensibly created?

One explanation could be that Durin VII, “Durin the Last,” was added to later versions of the Red Book of Westmarch. Yet, if this addition occurred later, why are there no dates associated with Durin VII, unlike other figures in the Durin Family Tree? Furthermore, how was it known that there would be a seventh Durin, and more significantly, that he would be the last, especially considering the Dwarvish belief in Durin’s recurring incarnations?

According to Appendix A, the genealogical table is described as:

The Line of the Dwarves of Erebor as it was set out by Gimli Glóin’s son for King Elessar.

The genealogical table for Durin

The genealogical table for Durin

This attribution to Gimli aligns with the timeline provided in the appendices. The latest definitive date mentioned is Gimli’s departure in F.A. 120, which also marks the year of Aragorn’s death. It’s plausible that Gimli compiled this Durin family tree for Aragorn sometime between F.A. 91 (Dwalin’s death) and F.A. 120. The F.A. 120 entry for Gimli himself, along with a Third Age reckoning, was likely added later, possibly before F.A. 172, when the Red Book was copied for the Shire records.

This timeline deepens the Durin mystery. It suggests Gimli himself added Durin VII to the genealogy, even without a birth date for him. While a later scribe could have annotated Gimli’s work with “Durin VII & Last,” the absence of dates and the death of Thorin III Stonehelm remains puzzling.

Thorin III was likely still alive when Gimli departed, being 275 years old in F.A. 120, a considerable but not impossible age for a Dwarf. By F.A. 172, Thorin III would be 327, making his demise more probable. The undated entry for Durin VII implies either the text wasn’t annotated after Gimli, or a Gondorian scribe overlooked adding Durin VII’s dates, an unlikely oversight.

Therefore, it’s almost certain Gimli inscribed “Durin VII & Last,” even though Durin VII was not yet king when Gimli left Middle-earth. The question remains: how did Gimli know about Durin VII and this final epithet?

To understand this, we must consider the unique beliefs of Durin’s Folk concerning their first king, Durin I, “the Deathless.” Dwarvish tradition held that Durin I was indeed, in a sense, deathless.

There he lived so long that he was known far and wide as Durin the Deathless. Yet in the end he died before the Elder Days had passed, and his tomb was in Khazad-dûm; but his line never failed, and five times an heir was born in his House so like to his Forefather that he received the name of Durin. He was indeed held by the Dwarves to be the Deathless that returned; for they have many strange tales and beliefs concerning themselves and their fate in the world.

The Lord of the Rings, Appendix A: III ‘Durin’s Folk’, by J.R.R. Tolkien

The Silmarillion further elaborates on this belief, suggesting a form of reincarnation or cyclical return:

For they say that Aulë the Maker, whom they call Mahal, cares for them, and gathers them to Mandos in halls set apart; and that he declared to their Fathers of old that Ilúvatar will hallow them and give them a place among the Children in the End. Then their part shall be to serve Aulë and to aid him in the remaking of Arda after the Last Battle. They say also that the Seven Fathers of the Dwarves return to live again in their own kin and to bear once more their ancient names: of whom Durin was the most renowned in after ages, father of that kindred most friendly to the Elves, whose mansions were at Khazad-dûm.

The Silmarillion, ‘Of Aulë and Yavanna,’ by J.R.R. Tolkien

This raises questions about the nature of Durin’s return. Was it reincarnation, regeneration, or something else? Tolkien himself explored different interpretations. Initially, he leaned towards reincarnation:

For the Dwarves asserted that the spirits of the Seven Fathers of their races were from time to time reborn in their kindreds. This was notably the case in the race of the Longbeards whose ultimate forefather was called Durin, a name which was taken at intervals by one of his descendants, but by no others but those in a direct line of descent from Durin I. Durin I, eldest of the Fathers, ‘awoke’ far back in the First Age (it is supposed, soon after the awakening of Men), but in the Second Age several other Durins had appeared as Kings of the Longbeards (Anfangrim). In the Third Age Durin VI was slain by a Balrog in 1980.

The Peoples of Middle Earth, Chapter XIII, “Last Writings”, by J.R.R. Tolkien, ed. Christopher Tolkien

Later, Tolkien considered a different concept, moving away from reincarnation towards a form of “regeneration” or preservation:

The matter of the Dwarves, whose traditions (so far as they became known to Elves or men) contained beliefs that appeared to allow for re-birth, may have contributed to the false notions above dealt with. But this is another matter which already has been noted in the Silmarillion. Here it may be said, however, that the reappearance, at long intervals, of the person of one of the Dwarf-fathers, in the lines of their Kings – e.g. especially Durin – is not when examined probably one of rebirth, but of the preservation of the body of a former King Durin (say) to which at intervals his spirit would return. But the relations of the Dwarves to the Valar, and especially to the Vala Aulë, are (as it seems) quite different from those of Elves and Men.

The Nature of Middle-earth, Part Two, Chapter XV, “Elvish Reincarnation,” by J.R.R. Tolkien, ed. Carl F Hostetter

The precise mechanism of Durin’s return remains ambiguous. The “regeneration” hypothesis presents its own challenges. If it were simply the same body reawakening, it seems like it would be more verifiable and less mystical. The reincarnation idea, while still fantastical, allows for a degree of mystery and belief, aligning more with the Dwarvish perspective presented in Tolkien’s works.

Consider Durin VI, famously known for “Durin’s Bane.” He was slain by a Balrog. Could a body, even a Dwarvish one, regenerate from such destruction? Even if regeneration were possible, the body would have been lost in Moria, unlikely to be recovered with a Balrog present. And even if recovered, where would it be kept safe from dragons and other calamities that befell Dwarven kingdoms?

Succession also becomes complicated with the “regeneration” idea. If Durin reawakens, what happens to the current king or heir? Tolkien acknowledged this issue, suggesting that Durin’s return might only occur when there was no direct heir:

The Dwarves add that at that time Aule gained them also this privilege that distinguished them from Elves and Men: that the spirit of each of the Fathers (such as Durin) should, at the end of the long span of life allotted to Dwarves, fall asleep, but then lie in a tomb of his own body, at rest, and there its weariness and any hurts that had befallen it should be amended. Then after long years he should arise and take up his kingship again.(25)

25. [A note at the end of the text without indication for ‘its insertion reads:] What effect would this have on the succession? Probably this ‘return’ would only occur when by some chance or other the reigning king had no son. The Dwarves were very unprolific and this no doubt happened fairly often.

The Peoples of Middle-earth, Chapter XIII

While Dwarvish lack of prolificacy makes this succession solution somewhat plausible, it still feels less satisfying. The line of succession would effectively shift from Durin I to Durin VI (or whichever Durin regenerates), disrupting the continuous lineage back to Durin I depicted in the Durin family tree.

The reincarnation hypothesis, despite potential theological complexities within Tolkien’s Catholic framework, feels more narratively coherent and thematically resonant. Tolkien explored similar concepts with Elvish reincarnation, ultimately settling on “rebodying.” Perhaps he grappled with Dwarvish reincarnation and sought a distinct system, but the “regeneration” idea remains less convincing.

Ultimately, the ambiguity of the “reincarnation” option is appealing. It leaves room for the possibility that Dwarvish belief is just that – a belief, not necessarily objective truth. The “regeneration” idea, conversely, leans towards a more concrete, less mythical reality.

Regardless of the mechanism of Durin’s return, the question of Durin VII and his epithet “the Last” remains. The answer, though brief, is revealing. The Peoples of Middle-earth provides a crucial insight:

For the Dwarves asserted that the spirits of the Seven Fathers of their races were from time to time reborn in their kindreds. This was notably the case in the race of the Longbeards whose ultimate forefather was called Durin, a name which was taken at intervals by one of his descendants, but by no others but those in a direct line of descent from Durin I. Durin I, eldest of the Fathers, ‘awoke’ far back in the First Age (it is supposed, soon after the awakening of Men), but in the Second Age several other Durins had appeared as Kings of the Longbeards (Anfangrim). In the Third Age Durin VI was slain by a Balrog in 1980. It was prophesied (by the Dwarves), when Dain Ironfoot took the kingship in Third Age 2941 (after the Battle of Five Armies), that in his direct line there would one day appear a Durin VII – but he would be the last. Of these Durins the Dwarves reported that they retained memory of their former lives as Kings, as real, and yet naturally as incomplete, as if they had been consecutive years of life in one person.

The Peoples of Middle Earth, Chapter XIII: “Last Writings”

This passage reveals that the prophecy of Durin VII being the last was made during Dain Ironfoot’s reign. Gimli’s inclusion of Durin VII in the Durin family tree, with the epithet “Last,” stems from this Dwarvish prophecy.

This prophecy’s confidence is striking. Gimli’s certainty in including Durin VII suggests its widespread acceptance among Dwarves. While Dwarves are not typically portrayed as prophetic, this foretelling held significant weight. The prophecy, being recent and tied to Dain’s reign, is particularly noteworthy. Unlike a general prediction of another Durin, specifying him as the last is a profound declaration. No prior texts mention such a limitation on the Durin lineage.

This prophecy, therefore, hints at the decline and eventual end of the Dwarves as a people. While there’s no explicit rule preventing a Durin VIII, the Dwarves likely interpreted this prophecy as signifying the end of their line, perhaps due to their diminishing numbers and changing world. An early version of Appendix A supports this interpretation:

And the line of Dain prospered, and the wealth and renown of the kingship was renewed, until there arose again for the last time an heir of that House that bore the name of Durin, and he returned to Moria; and there was light again in deep places, and the ringing of hammers and the harping of harps, until the world grew old and the Dwarves failed and the days of Durin’s race were ended.

The Peoples of Middle Earth, Chapter IX: “The Making of Appendix A : (iv) Durin’s Folk”

Although the final Appendices lack such explicit details about the Dwarves’ end, hints of their decline in the Fourth Age are present. Tragically, the Dwarves seemed to foresee their own diminishment even during the War of the Ring.

The Third Age came to its end in the War of the Ring, but the Fourth Age was not held to have begun until Master Elrond departed, and the time was come for the dominion of Men and the decline of all other ‘speaking-peoples’ in Middle-earth.

LOTR, Appendix B, ‘The Tale of Years’

These details paint a poignant picture of the Dwarves’ awareness of their fading future. Themes of decline permeate Tolkien’s Legendarium, yet the Dwarves’ situation is particularly poignant. Men may diminish, but their ultimate fate is uncertain. Elves, though fading from Middle-earth, have Valinor. Dwarves have no such solace, yet they persevere with remarkable tenacity.

This tenacity is the beauty and tragedy of the Dwarves. Crafted by Aulë to be steadfast, they endure even as their world changes. They were destined to be secondary to Men, just as they were awakened after the Elves due to Aulë’s impatience.

While this blog isn’t solely focused on Dwarves, their story holds a deep fascination. Their tenacity and nobility in the face of inevitable decline are profoundly moving. They fight the “long defeat,” embodying it perhaps more than any other race in Middle-earth.

Tolkien’s Dwarves deserve greater recognition. The prophecy of Durin the Last reveals much about their character, their quiet heroism, and their acceptance of their fate. There is a hidden, sad, and noble story within Gimli’s inclusion of Durin VII in the Durin family tree – a truly Dwarvish story of triumph and inevitable failure.

The world is grey, the mountains old,

The forge’s fire is ashen-cold;

No harp is wrung, no hammer falls:

The darkness dwells in Durin’s halls;

The shadow lies upon his tomb

In Moria, in Khazad-dûm.

But still the sunken stars appear

In dark and windless Mirrormere;

There lies his crown in water deep,

Till Durin wakes again from sleep.