rose

rose

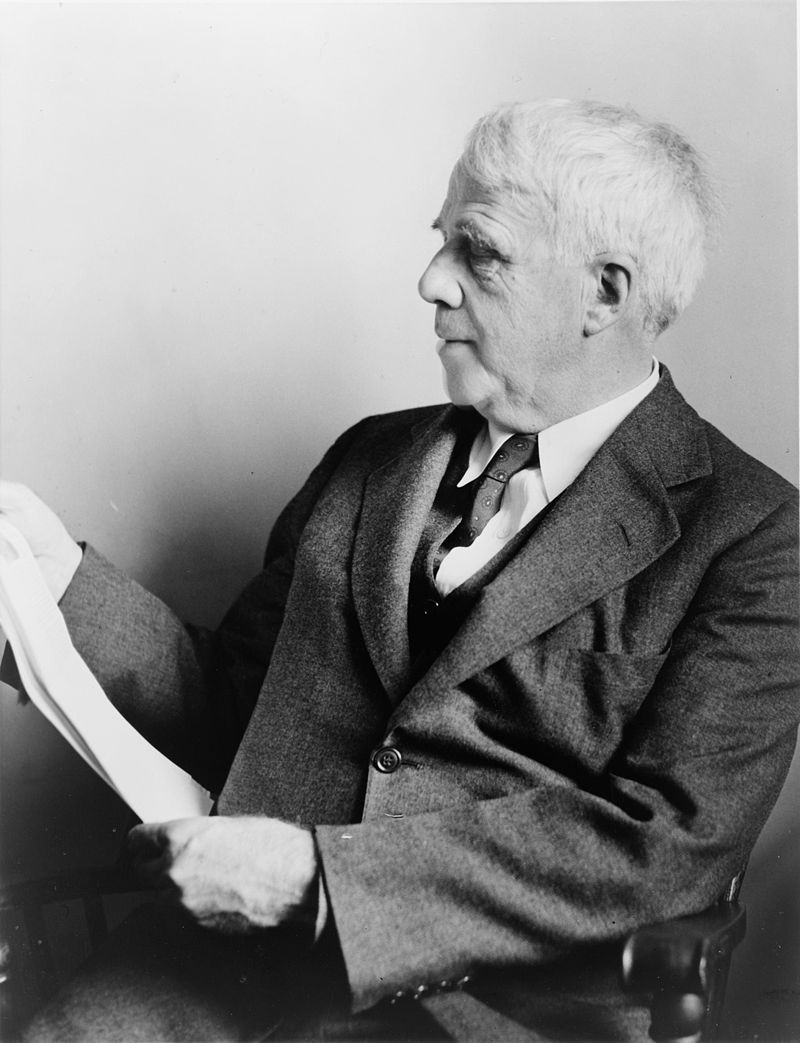

Robert Frost, a celebrated American poet, often used deceptively simple language to explore profound themes. His poem, “The Rose Family,” might initially seem like a whimsical take on botany, but it unfolds into a clever commentary on poetic tradition and the very nature of categorization. This seemingly lighthearted “Family Poem” is packed with layers of meaning, inviting readers to delve deeper into its intertextual wit and subtle critique.

The rose is a rose,

And was always a rose.

But the theory now goes

That the apple’s a rose,

And the pear is, and so’s

The plum, I suppose.

The dear only knows

What will next prove a rose.

You, of course, are a rose –

But were always a rose.

At its surface, the poem playfully engages with the biological classification of the Rosaceae family, which indeed encompasses not only roses but also fruits like apples, pears, and plums. This botanical fact serves as the launching point for Frost’s exploration of a more abstract question: what defines the essence of something? Is a scientific label enough to change our perception of reality? Just because botany groups apples and roses together, does it diminish the distinct identity of a rose, or elevate an apple to its romantic status?

The poem’s opening line, “The rose is a rose,” is a direct nod to Gertrude Stein’s famous line, “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose” from her poem “Sacred Emily.” Stein’s repetition is often interpreted as a modernist assertion of directness – a rose is simply a rose, devoid of layers of metaphor or symbolism. Frost, however, cleverly twists this idea. He acknowledges Stein’s sentiment but then immediately introduces the botanical perspective, suggesting that the definition of a “rose” is more fluid and scientifically constructed than Stein might have implied. He playfully challenges the notion of fixed categories, hinting that even something as seemingly self-evident as a rose can be re-categorized and re-understood.

Furthermore, “The Rose Family” subtly questions the overuse of the “rose” as a metaphor for beauty in poetry. For centuries, poets have likened loved ones and beauty itself to roses, often to the point of cliché. Frost’s poem gently satirizes this very tradition. By extending the “rose family” to include everyday fruits, he humorously suggests that if everything can be a rose, then the metaphor loses its special significance. Where do we draw the line in our poetic comparisons? If an apple is a rose, then the romantic comparison of a lover to a rose becomes less unique, almost commonplace.

This playful jab at poetic clichés becomes even clearer when considering the line, “You, of course, are a rose – But were always a rose.” This closing addresses a “you,” reminiscent of countless love poems where the beloved is compared to a rose. Frost’s speaker seems to participate in this tradition, yet the preceding lines have already subtly undermined the very metaphor he employs. The “you” being a rose “always” might sound like a timeless compliment, but within the poem’s context, it also echoes the potentially tired and unoriginal nature of such comparisons.

800px-robert_frost_nywts

800px-robert_frost_nywts

Robert Frost (1874-1963) was a quintessentially American poet, deeply connected to the landscapes and rhythms of rural life. His poetry, while accessible on the surface, often grapples with complex philosophical and social issues, earning him widespread acclaim and numerous Pulitzer Prizes. Anecdotally, his passion for poetry was so intertwined with his personal life that upon selling his first poem, “My Butterfly. An Elegy,” he immediately proposed marriage to Elinor, his future wife, demonstrating the profound role poetry played in his very being.

Through “The Rose Family,” Frost offers a witty and insightful exploration of language, categorization, and poetic convention. It’s a “family poem” not just in its botanical reference, but also in its playful examination of the family of poetic tropes and traditions. In just ten lines, Frost manages to be both humorous and profound, leaving readers to ponder the delicate balance between scientific classification, poetic expression, and the enduring allure – and potential overuse – of the timeless rose metaphor.