Darren Banks, a contemporary artist featured on hudsonfamily.net, masterfully intertwines familial and technological narratives through a compelling fusion of filmic and sculptural expression. His work, resonating with the essence of cinema, horror, science fiction, and the enigmatic dark, delves into the depths of imagery, seeking the latent possibilities within. Having previously engaged with Banks in discussions and collaborations on projects like The Palace Collection, How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, Empty Distances, and Palace Projects, our latest exploration delves into his recent creations inspired by his relative, the multifaceted Churton Fairman, also known as horror film actor and sculptor Mike Raven.

filmstill_Crucible_of_Terror_1971

filmstill_Crucible_of_Terror_1971

In this illuminating conversation, we uncover the intricate layers of Banks’s Evermore installation and The Object Echo, examining how he navigates the image of the sculptural object through a familial lens.

Sculpture in Cinema: Animating the Legacy of Mike Raven

CC: Your past endeavors have skillfully interpreted film through a sculptural language. However, Evermore seems to shift this focus, presenting sculpture within a cinematic framework. This is evident in the references to Churton Fairman/Mike Raven’s horror film history and the animation of his sculptures using manipulated film techniques. Could you elaborate on your fascination with the image of the sculptural object in this particular project, especially considering its familial roots?

DB: My primary aim was to investigate the dynamic relationship between Churton Fairman’s dual life as a horror film actor and a sculptor, all within the context of my own artistic practice. This new body of work began with a formal concept: to apply cinematic editing techniques to a series of short films showcasing Fairman’s sculptures. The original footage, captured in the 1990s, depicts the wooden carvings slowly rotating against a black backdrop. My initial plan was to employ editing techniques commonly found in horror films as a set of rules to transform the character of each sculpture. I experimented with techniques like the dolly zoom, famously used in Jaws (1975), the jump cut, prominent in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1962), and double exposure, seen in Vampyr (1932).

Untitled_NVprojects

Untitled_NVprojects

However, as the work progressed, my thoughts expanded beyond the mere effect of editing on the object. I began to contemplate how elements from Churton’s past life, his experiences and persona, might permeate and perhaps even haunt his sculptures. This familial connection became a crucial layer in the interpretation of the work.

Utilizing After Effects, I crafted more complex pieces. Radio Vibrations, for instance, portrays a sculpture physically reacting to radio waves, sound, and music. The sculptural vignette Talkie stages two figures engaged in conversation, embodying Churton and his interviewer as they discuss the history of pirate radio. Beta Blob is a metamorphosis, a visual nod to Fredric March’s transformation in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931) or Landis’s werewolf, reflecting the theme of transformation and identity that resonates with Raven’s own career shifts.

For me, the most compelling and poignant sculptures emerged from simplicity. Pirouette, a two-sided spinning sculpture, exemplifies this. By accelerating its rotation, the two sides merge, creating a new image where Churton’s and my sculptures coexist, each retaining individual meaning while simultaneously in motion and static. In Match-cut, two seemingly unrelated images flicker, creating an uncanny optical illusion of a looping whole, a visual metaphor for the intertwined familial narratives.

By embracing simplicity in effects, I gained a deeper understanding of how movement shapes our perception of an object and how it enables us to perceive a three-dimensional object in space. The loop, spin, and repetition became integral to comprehending form. Essentially, movement provides the illusion of a 2D image becoming a 3D object, revealing how film can transform into sculpture. This process, deeply rooted in exploring my familial artistic link, has brought me closer to my intention of sculpting with film.

The Uncanny Object: Horror and the Familial Specter

CC: There’s a distinct displacement of the original sculptural image in this work. I’m particularly intrigued by how imbuing movement into static images conjures an uncanny image, seemingly animating an inanimate, “dead” object. This strongly suggests a connection to the horror genre, a genre deeply associated with Raven. Could you comment on this and your/Raven’s relationship to horror film, especially within this familial context?

As a sculptor, I’ve always been drawn to this concept of animating the inanimate. My transition into filmmaking was a natural progression, driven by the need to infuse movement into static objects. This brings me back to my earlier film Interiors (2005). I’ve long been fascinated by how horror films generate emotional intensity through lighting, sound, camera work, and architecture, imbuing objects with life through atmosphere and tension. For me, the way horror film layers these effects is inherently sculptural – consider a slow tracking shot around architecture, mapping space to build suspense.

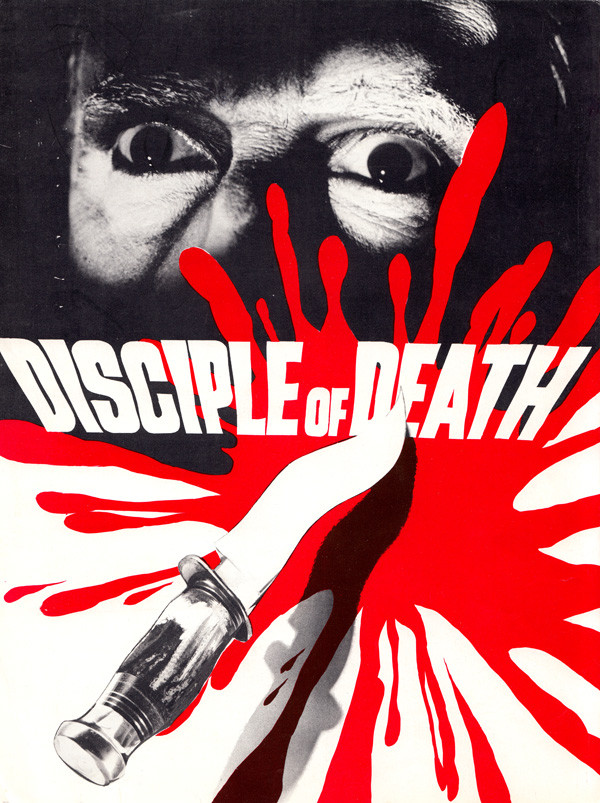

Discipleofdeath

Discipleofdeath

I recently attended a Dario Argento event at the BFI, where he showcased a scene from Tenebre (see clip) which, in my view, perfectly illustrates this layering of effect. This resonates deeply with the familial connection to horror through Raven.

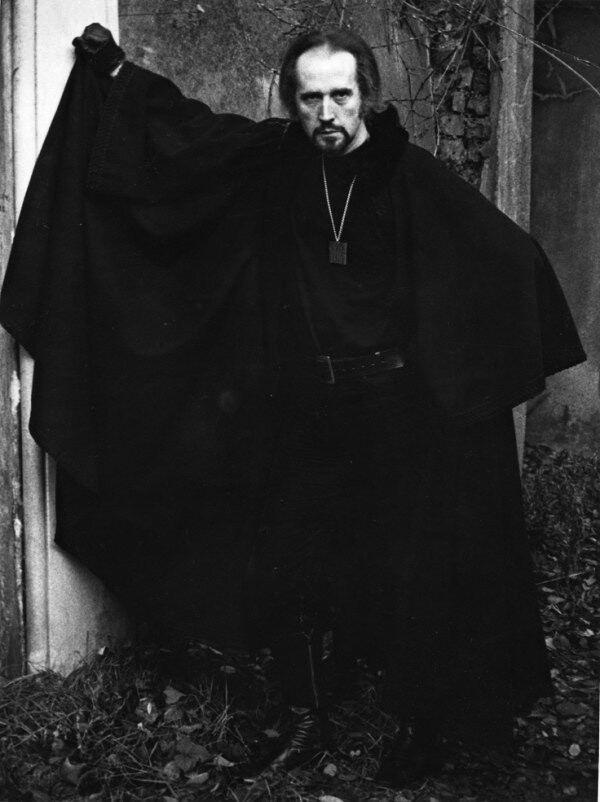

Churton Fairman, or Mike Raven, was always Dracula, never Frankenstein. I’m uncertain what he would have thought about bringing inanimate objects to life, though I’ve heard he owned a signed Aleister Crowley book, so perhaps he would have appreciated my “tin pot alchemy”! Rumors even circulated about Churton practicing the black arts, likely hearsay or part of a PR strategy during his British horror film actor phase. Interestingly, I was impressed to discover that one of Mike’s favorite films was Witchfinder General. It’s a brilliant film, and I’m also a great admirer of Michael Reeves, a remarkably talented director whose early death tragically curtailed a promising career. This shared appreciation for British horror cinema further underscores our familial artistic connection.

To my knowledge, Mike starred in only four horror films (Lust for a Vampire, 1971; I, Monster, 1971; Crucible of Terror, 1971; and Disciple of Death, 1972), but I find something intimate and focused about this small but impactful horror filmography. Crucible of Terror, a film I know you’ve previously written about, particularly stands out and directly relates to your question. It’s a 1970s English take on Bucket of Blood, where Mike plays an obsessed artist seeking perfection, who murders a woman by casting her in bronze while she’s still alive. While the film veers into a somewhat conventional revenge thriller, there are compelling scenes of people being killed by and for art, alongside portrayals of the sculptor at work and gallery private views. Beyond the overt references to art and horror, the film resonated with me because of its unexpected parallels with Mike’s life trajectory. He became an artist years after playing this character, blurring the lines between fiction and reality, a serendipitous aspect of life that mirrors our familial artistic journey.

Technology and Image: Revealing the Medium

CC: Returning to objects, similar to your previous works, the monitors in Evermore and The Object Echo are visible components of the installation, making the technology itself part of the artwork. Is it crucial for you to expose the relationship between technology and the image, between the image’s production and its presentation, especially in the context of exploring familial artistic histories through these mediums?

DB: I believe these two exhibitions effectively answer that question. For me, there has always been a strong link between the image and its display method. Technology often becomes an integral element in the sculptural assemblage. However, recent projects using projectors have prompted me to consider how the object/film can exist beyond the confines of the cube, within diverse architectural structures. This exploration extends to how familial narratives can be projected and interpreted across different contexts.

I greatly enjoyed sourcing old CRT monitors from Baltic39 for The Object Echo, using them to recreate the sculpture’s storage shelving from the Fairman family home in Cornwall. This emphasized the physicality of the display and the medium on which the film was presented. The choice of Cathode Ray Television monitors was deliberate, not merely aesthetic, but to present the film in its original format, as it was initially shot for TV. Here’s a link to Curator William Copper’s blog discussing CRT monitors in relation to my show.

In contrast, Evermore at Workplace focused more intently on the sculpture and the effects I applied. It was liberating to detach the films from the TV screens and scale them up, examining the objects’ relationship with the gallery architecture. The monitors receded into the background as these small, spinning objects transformed into peculiar, monumental totemic signs. There was a shift in emphasis, moving away from Mike Raven’s persona and towards my own artistic process and interpretation of this familial legacy.

DSC01166

DSC01166

Familial Discovery and Documentary: Unearthing Mike Raven’s Later Life

CC: Given your fascination with horror, it’s remarkable that you are related to someone so closely associated with classic British B-movie horror films. How did you discover that Mike Raven was part of your family, and how did the documentary footage come into your possession? What do Raven’s and your family think about this project, which so deeply engages with familial history?

The revelation began with my Mum, who was working on our family tree with her second cousin. During a lengthy conversation about our extended family, it emerged that I was related to Churton Fairman, also known as Mike Raven—radio DJ, horror film actor, and sculptor—who passed away in 1997. My Mum, aware of my interests in sculpture and horror, thought I would be intrigued by Churton. I had never heard of him before, but a brief online search quickly revealed him to be a captivating figure with a rich and multifaceted life: a man who loved blues and R&B, transitioned from radio DJ to horror film actor (collaborating with icons like Lee & Cushing), and then left it all behind to become a sheep farmer and sculptor in Cornwall. His obituary in the Independent reads like a modern-day fairytale, highlighting the extraordinary chapters of his life.

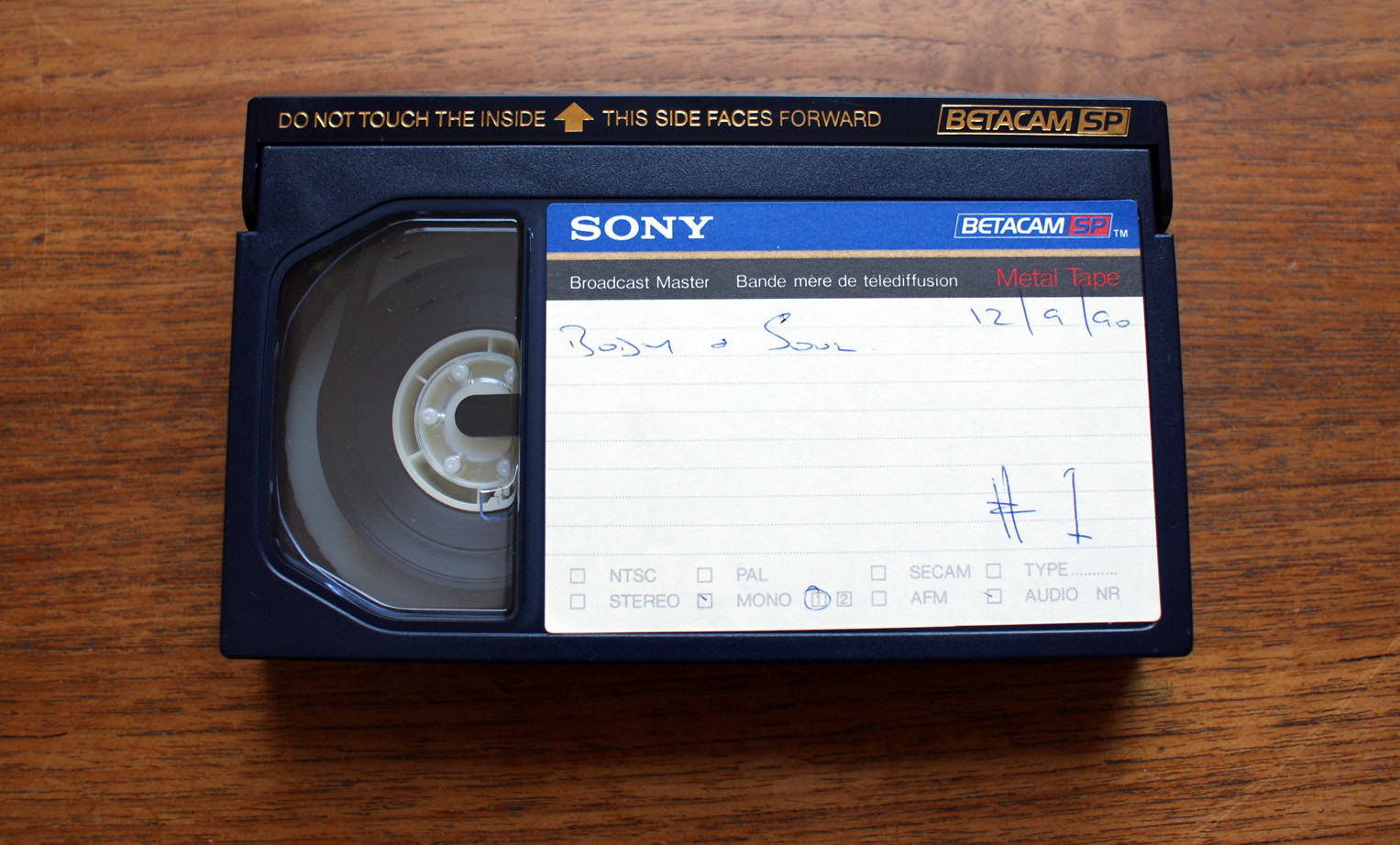

Following my initial research, I began to contemplate his life and our shared interests, though unsure of the direction to take. I started collecting his memorabilia, becoming a fan, gathering programs, records, DVDs, and posters from various phases of his career. Later, my Mum mentioned the documentary, revealing that in his later years, he was deeply involved in wood and stone carving. It turned out that in the early 1990s, with a friend’s help, he created a documentary about his life as a sheep farmer and sculptor. This footage, unedited on beta tape, had been stored at the family home in Cornwall for about a decade. I decided to visit and speak with my cousin, which led to her entrusting me with the documentary, giving me carte blanche to use it as I saw fit. With the invaluable assistance of LUX, who digitized all the footage pro bono (many thanks to LUX), I was able to create a new body of work and also undertake the completion of the documentary itself, bringing his familial artistic narrative full circle.

Future Directions: Preserving a Familial Artistic Legacy

CC: What are your upcoming projects? Do you intend to further explore Mike Raven’s history in future works, continuing this exploration of familial artistic lineage?

DB: Currently, I’m focused on finishing the documentary about Churton’s later life as a sculptor, aiming for completion early next year. I’m also collaborating with Ele Carpenter to have one of the sculptures placed in a museum collection. This would be my homage to Churton, ensuring his artistic work is preserved for future generations, solidifying his familial artistic legacy.

Mike Raven

Mike Raven

I’ve started to consider my work beyond the confines of horror film, revisiting ideas about collecting and archives. This theme has been evident across several projects and working processes, involving the accumulation of vast amounts of film footage, images, and objects, appropriating them into sculptural assemblages and film montages. From working with Churton’s documented life to reassembling museum objects for the Backwater exhibition in Northampton, and my ongoing work with Palace Video Label, these projects reflect a consistent engagement with archival material and its artistic potential.

And yes, I definitely envision working with more footage from the documentary, intending to delve deeper into different facets of his career. By synthesizing the diverse elements of Churton’s life, a contemporary figure emerges, which I find profoundly fascinating. I’m also keen to revisit his horror films and curate a film screening of his back catalog and favorite films, celebrating his contributions to the genre and our shared familial connection to it.

I’m currently finalizing an online curated project, the Annotated Palace Poster Project, where I’ve invited 15 artists to create a poster for one of the 15 films in the Palace Collection (a small library of horror films on the Palace video label). The participating artists include Jamie Shovlin, Michelle Hannah, John Russell, Flora Whiteley, and many more. These images will eventually accompany 15 short texts by artists and writers responding to the original films in a Palace Projects publication. The texts are diverse, contributed by individuals such as Gilda Williams, Ben Fallon, and Lorena Muñoz-Alonso. It’s been a rewarding experience collaborating with such talented people, and the next step is to consolidate everything into a publication, further solidifying these artistic dialogues and legacies.

Exhibition Image Credit: Untitled, NV projects, London Wooden Sculpture Courtesy of Mandy Fairman Photo Credit: Peter White