Have you ever paused to consider what seemingly disparate plants like maples, lychees, and soapnuts might have in common? As the vibrant hues of maple leaves herald the arrival of autumn, it might surprise you to discover the intricate connections within the plant kingdom, linking familiar trees to exotic fruits and even natural soaps. The Soapberry Family, scientifically known as Sapindaceae, is a captivating group that reveals these unexpected botanical relationships.

This plant family is truly one of nature’s most fascinating creations, encompassing nearly 2,000 diverse species. From the delectable lychee and its tropical fruit cousins like longan and rambutan, to the majestic maple trees gracing temperate landscapes, and the intriguing soapberries themselves, the Sapindaceae family showcases an astonishing range of forms and uses. Interestingly, this family shares a close kinship with the citrus family (Rutaceae), a relationship that becomes apparent when observing the glossy, robust leaves of certain Sapindaceae members, subtly echoing the foliage of citrus plants.

Hop Tree (Arfeuillea arborescens) Fruit

Hop Tree (Arfeuillea arborescens) Fruit

Image: The distinctive fruit of the Hop Tree (Arfeuillea arborescens), showcasing the splitting capsule and contrasting colors typical of the soapberry family, with hard black seeds encased in red, hairy outer layers.

The Delicious Diversity of Edible Fruits in the Soapberry Family

One of the most appealing aspects of the soapberry family is its contribution to the world of edible fruits. Several members of this family produce fruits that are not only delicious but are also gaining popularity in global markets. Lychee and rambutan, once exotic delicacies, are increasingly finding their place on American grocery shelves, introducing consumers to the unique flavors of the Sapindaceae.

Lychee Fruit with Pink Shell

Lychee Fruit with Pink Shell

Image: A close-up of a ripe lychee fruit, revealing its textured pink outer shell, a hallmark of this tropical delight from the soapberry family.

Lychee Aril and Seed

Lychee Aril and Seed

Image: An opened lychee fruit, displaying the translucent white aril, the edible fleshy part that surrounds the dark seed, characteristic of many fruits in the soapberry family.

The lychee, a tropical gem with a history of cultivation stretching back to the 11th century, is a prime example. Highly prized in ancient China, lychees were even transported by a special horse courier service during the Han dynasty to ensure their delivery as coveted gifts.

Longan Fruits (Dimocarpus longan)

Longan Fruits (Dimocarpus longan)

Image: Clusters of Longan fruits (Dimocarpus longan) hanging from a branch, showcasing their round shape and brown shells, another popular tropical fruit in the soapberry family.

The longan (Dimocarpus longan), another commercially significant fruit from Asia, shares a flavor profile similar to lychee. Its name, translating to “dragon eye” in Chinese, is derived from the fruit’s appearance when shelled, resembling an eyeball. Despite being cultivated for nearly two millennia, the longan is still relatively new to many parts of the world.

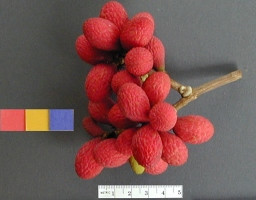

Rambutan Fruits (Nephelium lappaceum)

Rambutan Fruits (Nephelium lappaceum)

Image: Vibrant red Rambutan fruits (Nephelium lappaceum) with their characteristic spiky, hairy shells, a visually striking tropical fruit closely related to lychee within the soapberry family.

Often found alongside lychee in tropical regions is rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum). Its distinctive spiky red shell, covered in hairs that aid in transpiration, encloses a translucent white flesh, much like the lychee. Both lychees and rambutans are known for their short shelf life as fresh fruits, and cultivation attempts in the United States have faced challenges.

Rambutan and Lychee Comparison

Rambutan and Lychee Comparison

Image: A hand holding both rambutan and lychee fruits, demonstrating the similarity in their translucent white flesh and texture, yet distinct outer appearances, both belonging to the diverse soapberry family.

The taste and texture of both rambutan and lychee are often compared to grapes, but with a more pronounced floral aroma, adding to their exotic appeal.

Korlan Fruit (Nephelium hypoleucum)

Korlan Fruit (Nephelium hypoleucum)

Image: Korlan fruit (Nephelium hypoleucum) with its reddish-brown shell, an example of the diverse fruit variations within the rambutan-like species of the soapberry family.

Hairless Rambutan (N. xerospermoides)

Hairless Rambutan (N. xerospermoides)

Image: Hairless Rambutan (N. xerospermoides), showcasing a smoother, less spiky shell compared to typical rambutan, highlighting the variations within the soapberry family’s fruit diversity.

Pulasan Fruit (N. ramboutan-ake)

Pulasan Fruit (N. ramboutan-ake)

Image: Pulasan fruit (N. ramboutan-ake) hanging from a tree, displaying its reddish shell with short, fleshy spines, known for its sweetness and rarity outside Southeast Asia within the soapberry family.

Species related to rambutan include korlan (Nephelium hypoleucum), hairless rambutan (N. xerospermoides), and pulasan (N. ramboutan-ake). Pulasan, sweeter than both rambutan and lychee, is a rare find outside of Southeast Asia. Its name originates from the Malay word for “twist,” referring to the method of opening the fruit.

The ackee, or akee apple (Blighia sapida), holds a prominent place in Caribbean cuisine, most notably as part of Jamaica’s national dish, ackee and saltfish. This fruit offers a nutty flavor, and its cultivars are broadly categorized into “butter” or “cheese” types based on color and shelf life. However, caution is paramount when preparing ackee, as the unripe aril and other parts of the fruit contain toxins known as “soapberry toxins.” Proper preparation and cooking are essential, typically involving parboiling, frying in butter, or incorporating into stews and curries. The danger of consuming unripe ackee is so significant that it can lead to “Jamaican vomiting sickness,” also referred to as ackee sickness.

Ackee Fruit (Blighia sapida)

Ackee Fruit (Blighia sapida)

Image: Ackee fruit (Blighia sapida) with its partially opened pods, revealing the cream-colored arils that are edible when ripe and properly cooked, contrasting with the poisonous unripe fruit and seeds within the soapberry family.

Opened Ackee Fruit Pods

Opened Ackee Fruit Pods

Ackee and Saltfish Dish

Ackee and Saltfish Dish

Image: Ackee and Saltfish, the national dish of Jamaica, showcasing the cooked ackee arils mixed with salt cod, a culinary highlight featuring a member of the soapberry family.

Quenepa Fruits (Melicoccus bijugatus)

Quenepa Fruits (Melicoccus bijugatus)

Image: Quenepa fruits (Melicoccus bijugatus) in a bunch, resembling small limes in appearance, yet offering a lychee-like interior, demonstrating the surprising fruit forms within the soapberry family.

Quenepa (Melicoccus bijugatus) fruits, resembling limes in appearance, further illustrate the diverse fruit offerings of the soapberry family. While their exterior might suggest citrus, their interior is more akin to lychee, featuring a bittersweet, gelatinous flesh. Quenepa fruits are enjoyed fresh, canned, or used in refreshing beverages.

Beyond Fruits: Guarana, Fish Poison, and Other Uses

The versatility of the soapberry family extends beyond just fruits. Guarana, a natural stimulant comparable to coffee, and fish poisons derived from certain species, represent just a fraction of the diverse applications of these plants.

Guarana Beverage

Guarana Beverage

Image: A refreshing Guarana beverage, highlighting the use of Guarana (Paullinia cupana) from the soapberry family as a natural stimulant in drinks and supplements.

Guarana (Paullinia cupana), particularly prevalent in Brazil, boasts a caffeine concentration twice as high as coffee beans. It is a popular ingredient in energy drinks, herbal teas, and dietary supplements. Several Brazilian sodas feature guarana as a key ingredient. The name “guarana” originates from the indigenous Guaraní language, roughly translating to “fruit like eyes of the people” or “eyes of the gods,” inspired by the fruit’s split appearance resembling an eyeball.

Pitomba Fruit (Talisia esculenta)

Pitomba Fruit (Talisia esculenta)

Image: Pitomba fruit (Talisia esculenta), native to the Amazon basin, displayed with a cut-open fruit revealing its pulp, used both for fresh consumption and as a source of fish poison, showcasing dual uses within the soapberry family.

Another notable application of several soapberry family species is their use as fish poison. Saponins, found in the bark of plants like guioa (wild quince), have been traditionally used by indigenous communities, such as those in Australia, to stun fish, making them easier to catch. Foambark is aptly named due to the saponins in its bark, which create a foamy lather when wet, leading to its use as both soap and fish poison by indigenous Australians.

Buckeye Seeds

Buckeye Seeds

Ohio Buckeye Seeds (Aesculus glabra)

Ohio Buckeye Seeds (Aesculus glabra)

Image: Ohio Buckeye seeds (Aesculus glabra), smooth and brown, illustrating the seeds of a buckeye species, known for saponin content and traditional uses by Native Americans.

The California buckeye (Aesculus californica) and Ohio buckeye (Aesculus glabra) were also utilized by Native Americans for stunning fish. After careful boiling and leaching to remove saponin toxins, the seeds of these buckeyes could be ground into flour, similar to acorn meal, providing a source of food. However, without proper leaching, buckeye seeds readily release saponins, producing a lather when crushed and mixed with water.

Soapberries, Soapnuts, and Decorative Beads

Perhaps one of the most distinctive characteristics of the soapberry family is the presence of saponins in many of its members, leading to their use as natural soaps. This is particularly true for soapberries and soapnuts of the Sapindus genus.

Indian Soapberry or Washnut (Sapindus mukorossi)

Indian Soapberry or Washnut (Sapindus mukorossi)

Image: Indian Soapberry or Washnut (Sapindus mukorossi) fruits, displaying the berries used for their saponin content, highlighting the soap-producing properties of the soapberry family.

The Indian soapberry or washnut (Sapindus mukorossi), native to the lower Himalayas, is a prime example. Soapnuts are now commercially available as an eco-friendly and gentle alternative to laundry detergents. Unlike synthetic detergents, soapnuts are known to be color-safe.

Soapnut as Natural Dye

Soapnut as Natural Dye

Image: Soapnut used as a natural dye, imparting color to Tussar silk yarn, illustrating the diverse applications of soapnut beyond cleaning, including natural dyeing in the soapberry family.

Beyond their use as cleansers, soapnuts also serve as natural dyes, especially for materials like Tussar silk yarn and cotton. Tussar silk itself is sometimes added to soaps for its silky texture.

The seeds of some soapberry family members are also used for decorative purposes. Oahu soapberry seeds are strung into leis, while the seeds and fruits of the rerak species are fashioned into buttons and beads. Wingleaf soapberry seeds are similarly used to create buttons and necklaces, showcasing the ornamental potential of these plants.

Maples: A Surprising Member of the Soapberry Family

The inclusion of maples (Acer genus) within the soapberry family might come as a surprise. With approximately 130-160 species, mostly trees native to Asia, maples are a dominant tree genus in many regions.

Maple Tree

Maple Tree

Image: A vibrant Maple tree in full autumn foliage, showcasing the iconic fall colors of maples, a well-known genus within the diverse soapberry family.

While some classifications historically placed maples in their own family, Aceraceae, modern plant taxonomy, with its refined research techniques, generally recognizes them within the Sapindaceae. This highlights the ever-evolving nature of scientific understanding as new data emerges.

Samara of Acer acuminatum

Samara of Acer acuminatum

Image: A close-up of the samara (winged fruit) of Acer acuminatum, native to the Himalayas, illustrating the characteristic fruit structure of maples within the soapberry family.

Maples are easily recognized by their winged fruits, known as samaras or “helicopters.” These fruits, containing seeds enclosed in nutlets attached to papery wings, spin as they fall, facilitating wind dispersal. A single maple tree can produce hundreds of thousands of seeds, ensuring widespread propagation.

Boxelder Maple Female Flowers (Acer negundo)

Boxelder Maple Female Flowers (Acer negundo)

Image: Female flowers of a Boxelder maple (Acer negundo), highlighting the floral structures of maples, which often have both male and female flowers on the same tree within the soapberry family.

Silverleaf Maple Female Flowers (Acer saccharinum)

Silverleaf Maple Female Flowers (Acer saccharinum)

Image: Female flowers of a Silverleaf maple (Acer saccharinum), showing the delicate floral details of maple trees, which are typically monoecious, bearing both types of flowers.

Autumn Maple Leaves

Autumn Maple Leaves

Image: A collection of Autumn Maple leaves in various stages of color change, capturing the iconic fall foliage of maples, renowned for their vibrant seasonal displays in the soapberry family.

Maples are celebrated for their spectacular fall foliage. Many species, including Norway maple, silver maple, Japanese maple, and red maple, are popular ornamental trees. Collections dedicated to maples, known as aceretums, can be found in botanical gardens like the one at Harvard University Arboretum. Maple trees are central to “leaf-watching traditions” in regions like North America and Japan, where the custom of appreciating maple leaf colors is called “momijigari.”

Momiji at Ryōan-ji Temple in Kyoto

Momiji at Ryōan-ji Temple in Kyoto

Image: Momiji (Japanese maple leaves) at Ryōan-ji Temple in Kyoto, Japan, showcasing the cultural significance of maples in autumn foliage viewing traditions.

Maple Sap Tapping

Maple Sap Tapping

Image: Maple sap tapping from a Sugar Maple tree, demonstrating the traditional method of collecting sap for maple syrup production, a valuable product from the soapberry family.

Maple syrup, a beloved staple, is produced from the sap of certain maple species during early spring. Maple syrup production can range from small-scale backyard operations to extensive commercial setups with numerous taps and tubing systems leading to a “sugar house” where the sap is concentrated by boiling. It takes approximately 40 liters of sap to produce just 1 liter of syrup. While sugar maple and black maple are preferred for their high sugar content, other maples like sycamore maple, mountain maple, bigleaf maple, redleaf maple, and boxelder maple can also be used, albeit with varying sugar levels or syrup clarity.

Sugar Maple Tree

Sugar Maple Tree

Image: A Sugar Maple tree in its yellow fall foliage, highlighting this keystone species of eastern North American forests, valued for maple syrup production and ecological importance within the soapberry family.

Sugar maple, native to eastern Canada and U.S. hardwood forests, is a keystone species, playing a critical role in forest ecology. It requires cold winters with hard freezes for dormancy, and its seeds exhibit a unique germination behavior, sprouting only slightly above freezing temperatures. Sugar maples are also highly shade-tolerant, allowing them to germinate under dense canopies and persist until canopy gaps appear. Their deep roots draw water from lower soil layers, benefiting both the tree and surrounding vegetation. Beyond syrup, sugar maple seeds, after soaking and roasting, can be a snack, and young leaves and inner bark are also edible.

Bigleaf Maple Leaf (Acer macrophyllum)

Bigleaf Maple Leaf (Acer macrophyllum)

Image: A Bigleaf Maple leaf (Acer macrophyllum), displaying its exceptionally large size, characteristic of this maple species found along the Pacific coast of North America within the soapberry family.

Maple wood is also highly valued. Dried maple wood is used for food smoking, while hardwood species are used for durable items like butcher blocks, bowling pins, baseball bats, furniture, and decorative pieces. Maple is also considered a “tonewood,” prized for its acoustic properties in musical instruments like drums, guitar necks, and string instruments.

Japanese maples (Acer palmatum), with their diverse cultivars, are particularly popular ornamentals across Asia, prized for their varied leaf shapes, sizes, fall colors, and overall aesthetic appeal.

Horse Chestnuts and Buckeyes: Ornamental Beauties

Horse chestnuts and buckeyes (Aesculus genus) are further examples of the soapberry family’s diverse members. These trees and their hybrids are widely planted as ornamentals in temperate regions, particularly admired for their showy flowers.

Horse Chestnut Flowers (Aesculus hippocastanum)

Horse Chestnut Flowers (Aesculus hippocastanum)

Image: Flowers of the Common Horse Chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum), showcasing the upright flower spikes that make horse chestnuts and buckeyes popular ornamental trees in the soapberry family.

Horse Chestnut Fruits (Aesculus hippocastanum)

Horse Chestnut Fruits (Aesculus hippocastanum)

Image: Horse Chestnut fruits (Aesculus hippocastanum) in their spiky green husks, developing on a branch, illustrating the fruit structure of horse chestnut trees within the soapberry family.

In the UK, horse chestnut seeds, known as conkers, are used in the popular children’s game of the same name.

In conclusion, the soapberry family, Sapindaceae, is a testament to the incredible diversity and interconnectedness of the plant kingdom. From the sweet and sometimes toxic fruits to the practical uses of soapberries and the familiar beauty of maples and horse chestnuts, this family offers a wealth of botanical wonders.

**The Horse Chestnut Fairy**

My conkers, they are shiny things,

And things of mighty joy,

And they are like the wealth of kings

To every little boy;

I see the upturned face of each

Who stands around the tree:

He sees his treasure out of reach,

But does not notice me.

For love of conkers bright and brown,

He pelts the tree all day;

With stones and sticks he knocks them down,

And thinks it jolly play.

But sometimes I, the elf, am hit

Until I’m black and blue;

O laddies, only wait a bit,

I’ll shake them down to you!

*Cicely Mary Barker (1895-1973)*