Sly & the Family Stone weren’t just a band; they were a cultural phenomenon. Emerging from San Francisco in the late 1960s, they embodied the era’s ideals of integration, progressiveness, and unwavering optimism. Their music, a vibrant fusion of psychedelic rock, funky soul, and pop melodies, resonated deeply, placing them at the heart of converging cultural movements. This unique sound propelled them to the top of the charts with a string of hits. While their trajectory faced challenges and transformations, Sly & the Family Stone left an indelible mark on music history, redefining the possibilities of pop. Were they a funk band? A rock band? A pop band? The answer is brilliantly, all of the above. Let’s delve into some of their essential songs that showcase their groundbreaking sound and enduring legacy.

The Beau Brummels, “Laugh, Laugh” (1965)

Sly Stone producing The Beau Brummels early hit "Laugh, Laugh"

Sly Stone producing The Beau Brummels early hit "Laugh, Laugh"

Before leading the Family Stone to fame, Sly Stone, born Sylvester Stewart, tasted his first significant success in the music industry as a producer. At just 19 years old, he helmed the production of “Laugh, Laugh” for the San Mateo folk-rock group, The Beau Brummels. Stone’s journey began as a teenage guitarist playing gigs around San Francisco, which led him to Tom Donahue of Autumn Records. Donahue recognized Stone’s burgeoning talent and gave him a chance to produce. “Laugh, Laugh” was among Sly’s initial production ventures, and by early 1965, it had impressively climbed into the Top 20 charts. As Ben Fong-Torres noted in 1970, this single marked “the very first rock & roll hits out of… a city then known for little more than Johnny Mathis and Vince Guaraldi.” Even before the “San Francisco Sound” fully blossomed, Sly Stone was already laying its foundation.

“Rock Dirge” (circa 1965)

Sly Stone experimenting with instrumental compositions at Autumn Records in 1965"

Sly Stone experimenting with instrumental compositions at Autumn Records in 1965"

During his brief tenure at Autumn Records, Sly Stone utilized the studio facilities to explore his own musical ideas. This experimentation resulted in tracks like “Rock Dirge,” a compelling instrumental piece characterized by its funky, chattering rhythm. Likely created around 1965, “Rock Dirge” showcases Stone’s self-taught musical versatility, with him playing the distinctive, wheezing organ featured prominently in the song. These early explorations, including “Rock Dirge,” were later compiled on a 1975 release of Stone’s early works. “Rock Dirge” specifically gained traction among breakbeat DJs, leading to its release as a sought-after seven-inch single, highlighting the enduring funk foundation of Sly Stone’s musical DNA.

“I Ain’t Got Nobody” (1967)

Sly and the Family Stone's early single "I Ain't Got Nobody" on Loadstone label"

Sly and the Family Stone's early single "I Ain't Got Nobody" on Loadstone label"

With earnings from his production work at Autumn Records, Sly Stone established a home base for himself and his family in Daly City, just south of San Francisco. It was here that the Family Stone began to take shape in the mid-1960s. Their first official release was “I Ain’t Got Nobody,” a single on the local Loadstone label. This track, with its upbeat backbeat and rich vocal harmonies, serves as a precursor to the signature sound that would define the group’s later hits. While “I Ain’t Got Nobody” garnered local attention, its significance lies in capturing the nascent stages of Sly & the Family Stone’s distinctive style. This early track played a crucial role in attracting the attention of Epic Records, who signed Sly and the Family Stone in the same year, setting the stage for their national breakthrough.

“Underdog” (1967)

Sly and the Family Stone's "Underdog" from their debut album 'A Whole New Thing'"

Sly and the Family Stone's "Underdog" from their debut album 'A Whole New Thing'"

“Underdog” holds the distinction of being both the first single and the opening track of Sly and the Family Stone’s debut album, A Whole New Thing. It served as a bold and energetic introduction to the band. The song’s unconventional opening features saxophonist Jerry Martini playfully riffing on the children’s tune “Frère Jacques” before exploding into a full-fledged acid rock jam. Driven by powerful horns, dramatic vocal shouts, and a socially conscious message about underdogs striving to prove themselves, “Underdog” made a strong statement. George Clinton, in conversation with Family Stone biographer Jeff Kaliss, remarked that the song felt like “they were speaking directly to you personally,” highlighting its impactful and direct message. Although A Whole New Thing and “Underdog” didn’t achieve commercial success, they showcased the group’s immense creative potential, foreshadowing their imminent national breakthrough.

“Dance to the Music” (1968)

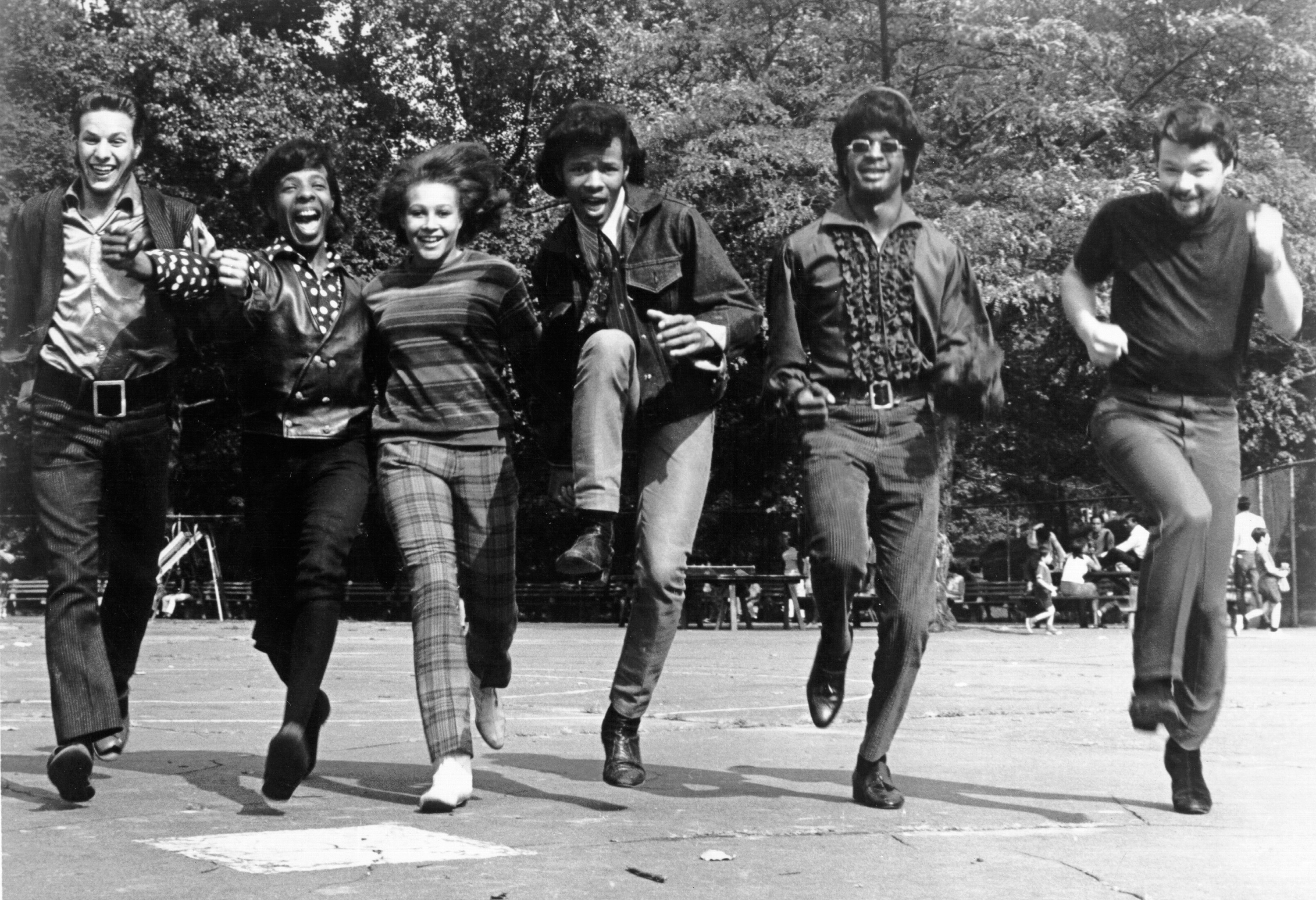

Sly and the Family Stone performing "Dance to the Music," their first Top 10 hit"

Sly and the Family Stone performing "Dance to the Music," their first Top 10 hit"

“Dance to the Music,” perhaps one of the most recognizable Sly Stone songs, became the group’s first Top 10 hit in the spring of 1968. This track, recorded under the guidance of Clive Davis, is characterized by its infectious and exuberant energy. While lyrically simple, essentially listing the instruments as they enter the groove—drums, guitar, bass, and so on—the song’s sheer vitality is undeniable. Within the band, opinions on “Dance to the Music” were mixed. Saxophonist Jerry Martini described it as “so unhip to us,” feeling it was a formulaic Motown-esque creation. However, engineer Don Pulese recounted Sly Stone’s own perspective, quoting him saying, “that’s the best bass and drum sounds I’ve ever got,” acknowledging the sonic achievement of the single. Regardless of internal debates, “Dance to the Music” cemented Sly & the Family Stone’s place in the mainstream.

“Dynamite” (1968)

Sly and the Family Stone's "Dynamite" from the album 'Life'"

Sly and the Family Stone's "Dynamite" from the album 'Life'"

The album Life, released between the breakthrough Dance to the Music and the masterpiece Stand!, often gets overlooked. Despite its commercial performance, Life resonated strongly with critics, including Rolling Stone‘s Barret Hansen (later known as Dr. Demento), who hailed it as “the most radical soul album ever issued.” Hansen was particularly captivated by the band’s element of surprise, evident in tracks like “Dynamite.” This psych-infused song, along with the album’s title track, is marked by unexpected shifts in arrangement and dynamic sonic pockets. The Family Stone’s vocal interplay further enhances this unpredictable quality. As trumpeter Cynthia Robinson explained, “We were free to adlib things. Sly would cut things off in a different way than the real recordings; he’d just stop it and go into something else,” highlighting the spontaneous and improvisational nature of their music.

“Everyday People” (1969)

Sly and the Family Stone performing "Everyday People," a utopian anthem"

Sly and the Family Stone performing "Everyday People," a utopian anthem"

“The things that were happening across the country changed us as people,” Freddy Stone reflected in a 2013 interview. “We would begin having conversations amongst ourselves, and Sly being the genius that he is, he was putting these thoughts into songs.” This period of reflection and social awareness culminated in the album Stand!. Released in 1969, Stand! absorbed the intense energies of the era’s political and musical upheavals, delivering an LP so potent that over half of its tracks were reissued on their Greatest Hits album just a year later. “Everyday People” stands as the epitome of this era for the group, a celebratory and utopian anthem promoting unity amidst diversity. Its message of acceptance and harmony, combined with its infectious groove, made “Everyday People” a timeless classic and one of Sly & the Family Stone’s most beloved songs.

“Sing a Simple Song” (1969)

Sly and the Family Stone's funk-driven B-side "Sing a Simple Song"

Sly and the Family Stone's funk-driven B-side "Sing a Simple Song"

While “Everyday People” was a feel-good pop hit, its B-side, “Sing a Simple Song,” showcased the Family Stone’s raw funk power. As aggressive and driving as anything James Brown was producing at the time, “Sing a Simple Song” also highlighted Sly Stone’s studio experimentation, particularly his use of stereo panning to separate instruments into distinct channels. Drummer Greg Errico, whose powerful drum work on the track has been sampled extensively, noted, “The track was laid so down to the bone and we all knew it was. You could feel it.” This raw, stripped-down funkiness made “Sing a Simple Song” a standout track and a favorite among musicians and DJs for its powerful groove.

“Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey” (1969)

Sly and the Family Stone's provocative and direct "Don't Call Me Nigger, Whitey"

Sly and the Family Stone's provocative and direct "Don't Call Me Nigger, Whitey"

While Stand! featured social commentary in various forms, “Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey” offered a stark and unambiguous message. At nearly six minutes long, the song is built around a repetitive, almost hypnotic hook, punctuated by a brief verse from Rose Stone. Its defiant and direct tone contrasts sharply with the album’s more optimistic tracks. “Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey” is also notable for its innovative use of vocoder effects and distorted instrumentation, elements that foreshadowed the emergence of P-Funk by nearly half a decade. This track demonstrated Sly & the Family Stone’s willingness to tackle controversial issues head-on and their pioneering approach to sound experimentation.

“I Want to Take You Higher” (1969)

Sly and the Family Stone performing "I Want to Take You Higher" at Woodstock"

Sly and the Family Stone performing "I Want to Take You Higher" at Woodstock"

“I Want to Take You Higher” is not only one of Sly & the Family Stone’s signature songs but also a legendary performance moment, most famously at Woodstock in 1969. The song’s origins trace back to an earlier, more abrupt version on Dance to the Music. During live performances, particularly at the 1968 Fillmore East show, the band began improvising and extending the song, adding the iconic line, “I wanna take you higher.” By the time of Stand!, “I Want to Take You Higher” had evolved into a more powerful and driving anthem, promising a transformative, almost forceful ascent to a higher plane. This song became a concert staple and a symbol of the band’s electrifying live energy.

“Hot Fun in the Summertime” (1969)

Sly and the Family Stone's summer anthem "Hot Fun in the Summertime"

Sly and the Family Stone's summer anthem "Hot Fun in the Summertime"

Capitalizing on the buzz from their Woodstock performance, Epic Records released “Hot Fun in the Summertime” as a standalone single in August 1969. In contrast to the socially charged themes of Stand!, “Hot Fun in the Summertime” delivered exactly what its title suggested: a lighthearted summer anthem filled with nostalgic warmth. Notably, it featured a rare instance of Sly Stone incorporating a string section into their sound. While some critics initially dismissed it as a pleasant but lightweight track, George Clinton later praised it as “proof that funk could be a pop standard,” recognizing its effortless blend of funk sensibilities with mainstream appeal.

“Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” (1970)

Sly and the Family Stone's groundbreaking funk track "Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)"

Sly and the Family Stone's groundbreaking funk track "Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)"

“Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” is instantly recognizable, not only for its unique, phonetic title but primarily for Larry Graham’s revolutionary bass playing. Graham’s “thunkin’ and pluckin'” technique transformed the role of the bass in R&B, elevating it to a lead instrument. Music scholar Ricky Vincent argues that “‘Thank You’ introduced the Decade of Funk,” highlighting its profound impact on shaping the funk genre in the 1970s. The song’s innovative bassline, combined with its driving rhythm and Sly Stone’s distinctive vocals, solidified its place as a funk classic and a pivotal moment in music history.

“Everybody Is a Star” (1970)

Sly and the Family Stone's uplifting anthem "Everybody Is a Star"

Sly and the Family Stone's uplifting anthem "Everybody Is a Star"

The Greatest Hits compilation of 1970 was so potent that it generated three entirely new hit songs, demonstrating Sly & the Family Stone’s incredible creative peak. Among these new tracks, “Everybody Is a Star” stands out as particularly timeless. Even more than “Everyday People,” “Everybody Is a Star” embodied Sly & the Family Stone’s optimistic and self-affirming spirit. It was a more joyful, almost hippie-esque expression of the “black is beautiful” movement. While “Everybody Is a Star” marked a high point, it also preceded a period of change and internal strife for Sly & the Family Stone, hinting at a shift towards darker and more introspective music.

6ix, “I’m Just Like You” (1970)

Sly Stone experimenting with drum machines on 6ix's "I'm Just Like You"

Sly Stone experimenting with drum machines on 6ix's "I'm Just Like You"

Following the Greatest Hits album, Sly & the Family Stone were expected to release a new studio album in 1970. However, Sly Stone opted to postpone the recording and relocate to Los Angeles. This move marked the beginning of internal tensions within the band. During this period of seclusion, amidst personal struggles, Sly explored new musical technologies, particularly early drum machines. Still a novelty at the time, drum machines were not considered serious studio instruments by many musicians. However, through his Stone Flower imprint, Sly began to experiment with their musical possibilities, as evidenced in the single “I’m Just Like You” by the vocal group 6ix. Sly’s innovative approach to music technology during this period foreshadowed the sonic direction of Sly & the Family Stone’s next groundbreaking album, There’s a Riot Goin’ On.

“Family Affair” (1971)

Sly and the Family Stone's introspective hit "Family Affair"

Sly and the Family Stone's introspective hit "Family Affair"

Greil Marcus famously described There’s a Riot Goin’ On as an album that “was no fun. It was slow, hard to hear, and it isn’t celebrating anything.” He meant this as high praise, recognizing the album’s darkness as an honest reflection of the Family Stone’s internal struggles and the disillusionment of early 1970s America. “Family Affair,” the group’s last Number One single, epitomized this shift. It was a stark departure from the sunny optimism of “Everybody Is a Star,” replaced by a somber meditation on human vulnerability and conflict, cleverly disguised by the mesmerizing pulse of its drum machine rhythms. Despite Sly’s insistence in a 1971 interview that he didn’t feel “torn apart,” “Family Affair” and the Riot album suggested a deeper internal turmoil.

“Running Away” (1971)

Sly and the Family Stone's musically upbeat but lyrically cynical "Running Away"

Sly and the Family Stone's musically upbeat but lyrically cynical "Running Away"

“Running Away,” even more than “Family Affair,” presented a stark contrast between its lyrical content and musicality. The message was clear: “running away/to get away … you’re wearing out your shoes,” accompanied by mocking “ha-ha, hee-hee” laughter. However, the music itself was surprisingly bright and cheerful, featuring a jaunty guitar and vibrant brass section reminiscent of Earth, Wind & Fire. This juxtaposition of cynical lyrics with upbeat music created a unique and unsettling effect, showcasing the complexities of Sly & the Family Stone’s evolving sound during this period.

“Luv N’ Haight” (1971)

Sly Stone's hazy and layered sound on "Luv N' Haight" from 'There's a Riot Goin' On'"

Sly Stone's hazy and layered sound on "Luv N' Haight" from 'There's a Riot Goin' On'"

During his period of seclusion in his Los Angeles studio, Sly Stone experimented extensively with playing multiple instruments himself. While There’s a Riot Goin’ On still credited the Family Stone members, many tracks were primarily Sly overdubbing various instrumental parts. With each added layer, the sound quality intentionally degraded, resulting in the hazy, drug-induced sonic landscape of tracks like “Time,” “Thank You for Talkin’ to Me Africa,” and “Luv N’ Haight.” These songs, characterized by their slurred and dreamlike quality, were both alluring and unsettling, representing a journey into the darker side of funk and Sly Stone’s increasingly experimental production techniques.

“If You Want Me to Stay” (1973)

Sly and the Family Stone's "If You Want Me to Stay" reflecting Sly's detachment"

Sly and the Family Stone's "If You Want Me to Stay" reflecting Sly's detachment"

The original Family Stone began to fracture during the Riot era, marked by a series of chaotic and poorly managed concerts. For his next album, Fresh, Sly returned to the Bay Area but started replacing key band members who had been with him since the “Dance to the Music” days. Despite personnel changes, Fresh continued the funk explorations of Riot, though with a slightly less dark and intense tone. “If You Want Me to Stay,” the album’s modest hit, still reflected Sly’s detached persona. As he explained in a radio interview, “That’s exactly what I meant, what I wrote. If you want me to stay, let me know. Otherwise, sayonara,” revealing a sense of distance and uncertainty.

“Can’t Strain My Brain” (1974)

Sly and the Family Stone's "Can't Strain My Brain" from their final group album of the 70s"

Sly and the Family Stone's "Can't Strain My Brain" from their final group album of the 70s"

Small Talk, Sly and the Family Stone’s final group album of the 1970s, received lukewarm reviews. A Billboard review in July 1974 noted “not really much new in the way of presentation… but… there really is no need for a successful star to have to come up with something new on each LP.” While Small Talk largely revisited familiar stylistic territory, tracks like “Can’t Strain My Brain” still showcased the band’s tight musicianship. The song, like many of Sly’s songs from this era, hinted at his increasingly tenuous grip on reality, adding a layer of personal reflection to the music.

“Remember Who You Are” (1979)

Sly Stone reuniting with siblings for "Remember Who You Are" in 1979"

Sly Stone reuniting with siblings for "Remember Who You Are" in 1979"

Arguably the last great Sly Stone song, “Remember Who You Are,” was not a full return to the original Family Stone sound. Sly had disbanded the group years prior and had been recording under his own name. His 1976 album, Heard Ya Missed Me, Well I’m Back, with its overly literal title, was not well-received. However, Back on the Right Track in 1979 signaled a potential return to form. For “Remember Who You Are,” Sly reunited with siblings Freddie and Rose Stone, recapturing some of the original Family Stone magic. This track serves as a poignant reminder of the band’s enduring legacy and the unique musical chemistry they created.